In today’s The Dreaming #3, Simon Spurrier, Bilquis Evely, Mat Lopes, and Simon Bowland continue building upon the world of The Sandman in familiar yet simultaneously unexpected and topical ways. From the introduction of new characters to the re-imagining of figures from The Dreaming’s past, this creative team has set out to craft a series that feels timeless, yet ultimately reads as quite timely as well.

Recently, the Beat had a chance to sit down with Spurrier to discuss the philosophical ideas and political history that inform The Dreaming.

Alex Lu: One of the seemingly contradictory things that I loved about the original Sandman stories was how unafraid it was to be provocatively political and contemporary despite its mythology largely being rooted in archetypical fables and fairy tales that have been in our cultures for hundreds of years. And it seems safe to say that you and the rest of The Dreaming creative team have carried that element of The Sandman’s identity into your book. Was that always a part of your team’s pitch for this version of The Dreaming or was it something that was born in the telling of these characters’ arcs?

Simon Spurrier: Interesting point. I think I’d actually argue that one of the great strengths of Sandman is that it carefully refuses to be Of A Particular Time, dancing between the raindrops of date and detail. It’s as relevant today as it was when it was released (some of the haircuts notwithstanding) precisely because it was less interested in the minute vicissitudes of “now” than in the big Human Condition stuff. It asks: what is it to be a thinking, idea-having creature, with a sense of consciousness which often seems distinct from one’s physical life? How does wonder change the way you live? And to whom do you make your votive offerings when all you have to give are stories? That’s Sandman, and it needs no timestamp.

Neil’s perfectly placed to take a longterm view on the success of a property like this, by the way, and that led to a piece of advice he gave the new team very early on: focus on stories which (like the original series) will still be sitting on a shelf in twenty years feeling fresh, rather than on flash-bang-wallop of single issue sales given a boost by thinly-veiled zeitgeists. (Even when used right, “contemporary” is a dangerous word.)

My approach was to settle quickly on the base-of-the-iceberg stuff which I believe to be true and important, irrespective of The World Today, and to focus on that rather than the frosting of current events. For instance: I believe the world is indubitably a better place when it contains more variety, more openness, and more curiosity. I believe people are easily led into bad choices by manipulating their fear of otherness and their resistance to change. I believe a catastrophic lack of empathy is behind most human horror, and inept communication skills are behind the rest. These are eternally relevant biases which I can pour into any comic – especially one set in a place like the Dreaming (which after all is just the gross sum of all human stories) – and not feel as though the outcome will be dated within a couple of years.

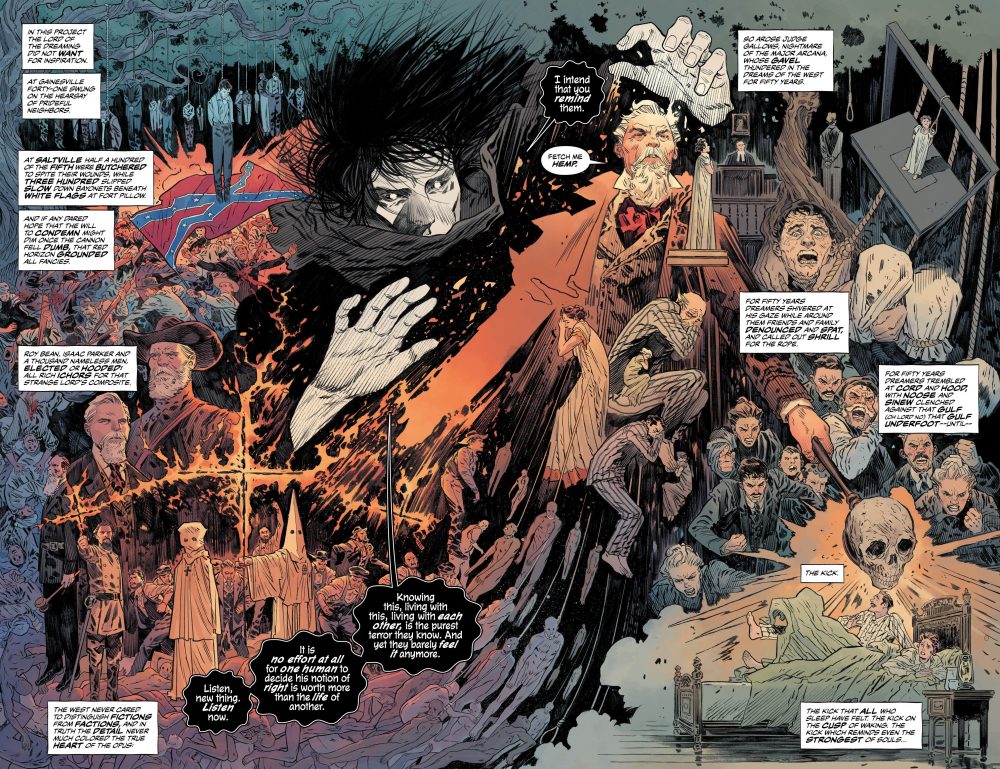

What’s quite interesting is that some people will find specific contemporary reference and relevance where none was intended. Judge Gallows is a great case in point. The Dreaming (at least its first arc) is the story of a Kingdom without a King, right? Things are quite scary for the residents. There’s an influx of strange influences, there are phenomena nobody can explain, there are suspicions of enemies both within and without, and those supposedly in charge are either weak, inadequate or keeping secrets. So: one of the Dreaming’s most down-to-earth residents, Merv Pumpkinhead, reacts as millions of people have in countless similar situations throughout history: he goes looking for a strong new leader to save him from the things he doesn’t like and doesn’t understand. Now: it would’ve been really easy to make this into a thinly veiled comment on the Trump presidency. And, hilariously, readers on both sides of the political spectrum have made that assumption. In fact, the primary reference we took for all this stuff was the unhappy Weimar Republic in the 1920’s and 30’s (which – in being mistaken for an analogy of today’s world – should raise a few frightened eyebrows). But, again, historical specificity isn’t really what the Sandman Universe is all about. Like I said: empathy matters – that’s the only bias I’m pushing with this stuff. I want Mervyn’s choice to feel plausible, justifiable, and right for him – even whilst the other characters around him are horrified by it. Even Gallows should feel as though he’s operating from a recognisably human position — ie: reacting to a perceived problem with a mixture of fear and iron self-belief, nobody can fix this but me — because no one is the villain of their own story.

I guess the short version of this (sorry) long answer is that all successfully tales are ultimately archetypes if you look hard enough, and there’s a lot less difference between mythology, history, and current events than you might think.

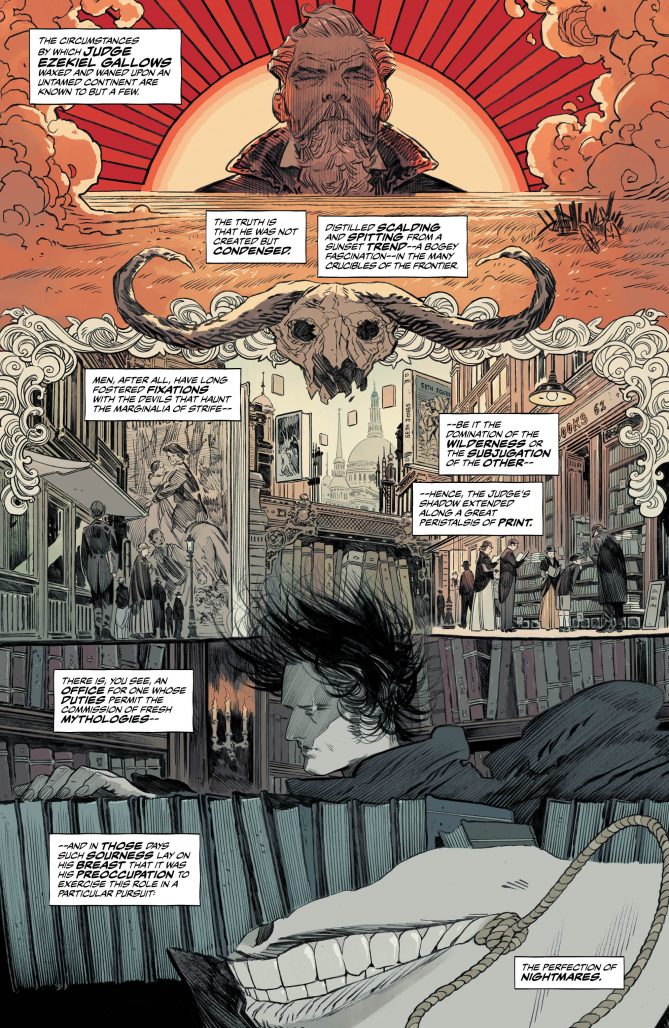

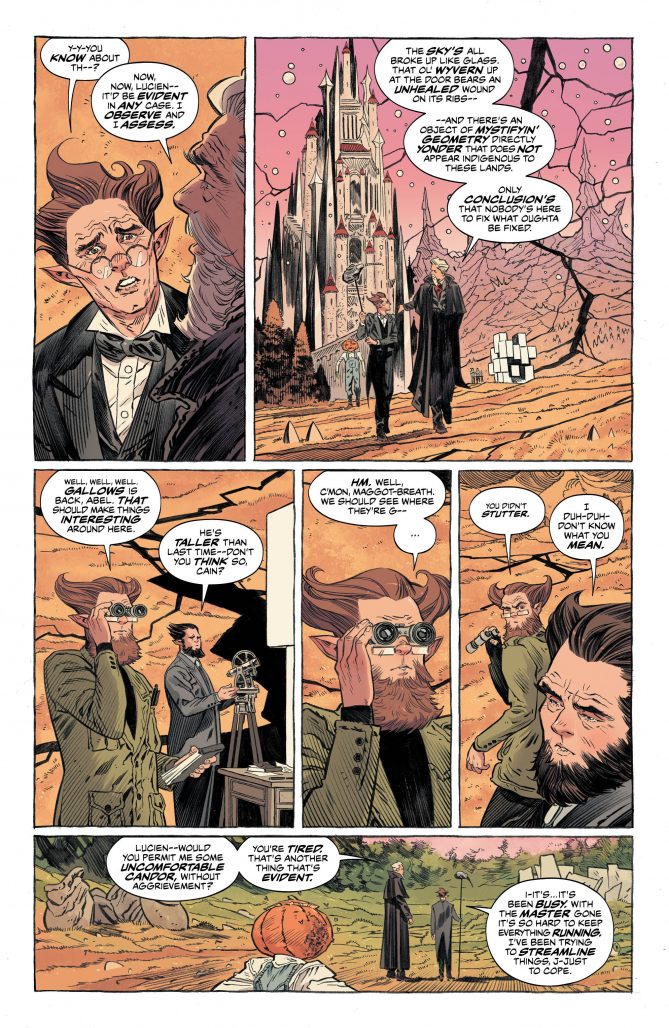

Lu: In The Dreaming #3, we learn a lot about Judge Gallows’ creation and his subsequent violent history in a short span of time thanks to your deft script and Bilquis Evely’s lovely artwork. How did the two of you go about composing the double-page spreads in this issue that focus on Gallows’ past—figuring out what could be conveyed through text and what would be shown through the art?

Spurrier: Bilquis is one of those rare things: an infallible Net Improver. I always know that whatever insane nonsense I suggest in a script, she’ll not only take a fair shot at it, but make it a billion times better. For the double page spreads you mention I wrote some hellishly long descriptions of how it looked in my head – up to and including the fact we’d need some serious out-of-the-box thinking from our excellent letterer Si Bowland to get the reader’s eye flowing in a novel direction (something of a trademark in my recent work). My scripts always come with the proviso that they’re advice, not dictat. As I said, Bilquis manages to both use the suggestion and completely subvert it all at once. She’s a helluva talent, and I don’t think there’s anyone better suited to a story set in the Dreaming.

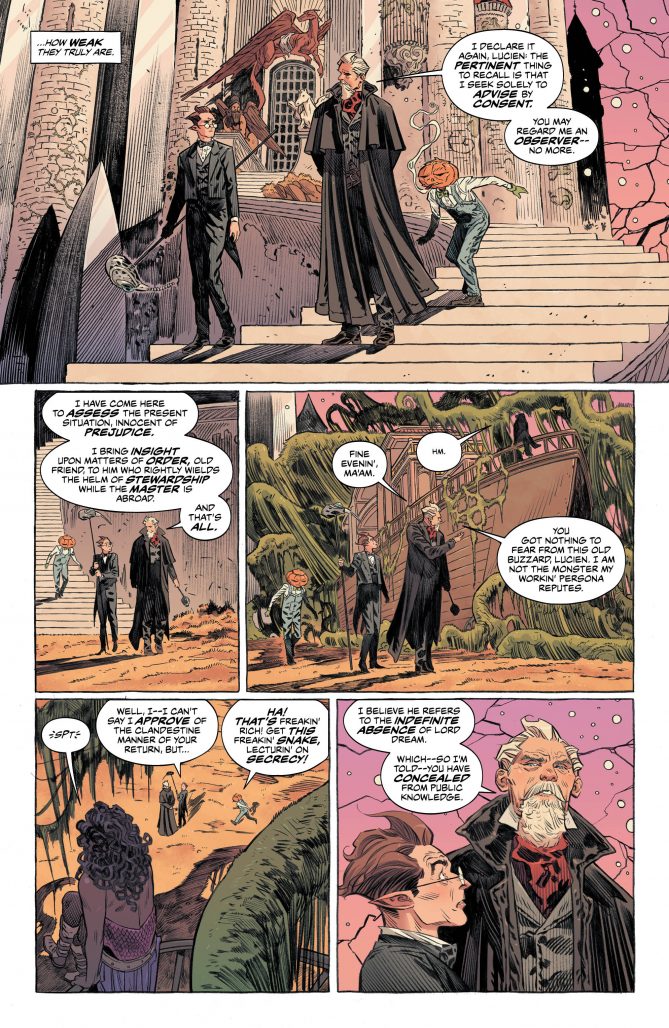

Lu: In The Dreaming #3, we get to dive a little deeper into Lucien’s head. In a lot of ways, his and Merv’s conflict over how to govern The Dreaming seems rooted in differing responses to the same problem—how to deal with displacement and a perceived loss of identity. And while those feelings of displacement have quickly lit a fire under Merv, pressuring him to react in a volatile way, Lucien’s breakdown feels like a much slower burn. Can you talk a bit about what you hope to explore through Lucien’s simmering internal conflict in contrast to the quick-burning inferno that has caused Merv to turn to Gallows?

Spurrier: I’m dreadfully fond of Lucien. I think somewhere between Dora’s damaged-but-won’t-admit-it breed of wounded-dog pissiness, and Lucien’s fragile (and decaying) need for neatness, is the closest I dare get to inserting myself into this story. They’re both expressions of the fear of losing control, if you get right down to it, and – because this is the Sandman Universe – in both cases “control” is reflected both in the mind and in the world around them. The difference lies in how they each respond to the knowledge of their own fallibility: Dora tries to ignore it, Lucien can’t. There’s nothing more tragic, in my opinion, than the decay of a brilliant mind, and it’s oh so much worse when the sufferer recognises it’s happening to them. One of the realest and most heartbreaking moments comes in issue 3, when Lucien gingerly admits to feeling secretly relieved when Gallows shows up to start taking over.

Lucien’s the ultimate unwilling steward, basically. He’s absolutely the best guy for the job – or, at least, was – but his exactitude and perfection also make him all too easy to knock aside. Brilliance can be brittle.

What’s interesting about Merv, in this context, is that both he and Lucien – like a lot of the characters in the Dreaming – are having to confront something extremely exotic: the fallibility of their own creator. Has Dream deserted them? Has he been overthrown, and if so – by whom?

Merv, being a practical soul, deals with these fears the same way he deals with everything: moaning and griping, sure, but also rolling up his sleeves and trying to do something about it. Bad call though it may turn out to be. Lucien has no such proactive option. He’s literally losing his mind and there are no leads as to where Dream’s gone – nor why. Like so many people who feel a personal relationship with their own creator, Lucien reacts to testing times by leaning even further into his faith. He’s becoming obsessed with the idea that by finding Dream – by restoring him to his throne – everything will be just fine. As we shall see, he’s prepared to go to quite extreme lengths to chase this goal.

Dora, who is not one of Dream’s creations, is spinning off in a third but just as dramatic direction. The joys of an ensemble cast, there.

Lu: To turn to the new inhabitants of The Dreaming, we’ve had the opportunity to spend some time at this point with Dora and watch what Merv refers to as the “soggies” mill around in the background, but their motivations and histories remain largely a mystery. What’s clear is their status in The Dreaming as refugees. And obviously, their very existence is under severe threat now that Judge Gallows has come to the scene. What are some of the challenges that have arisen in exploring such an intense and controversial topic through The Dreaming?

Spurrier: See my first answer splurge, I guess. Does something count as controversial if there’s literally never been a moment in the history of forever that it hasn’t been relevant? People have always moved around, and communities have always had a problem with strangers. The issue of human migration gives rise to stories (like pretty much all stories, actually) about how humans react to change. Do you take a risk and embrace variety, or play it safe and protect the status quo? There’s never been a time when that wasn’t a big deal. I just felt it was about time the Dreaming reflected it.

What’s interesting about the blank-faced arrivals is that they’re made of the same stuff as the rest of the Dreaming’s characters. We go back to this crazy perspective where a lot of these beings literally have a first-name relationship with their own god, Dream. Now that’s he’s disappeared there are all these weird entities sort of bubbling-up from the cracks in the world. They’re like incipient stories that have been restored to “Factory Settings”, whose only individuality comes from what they pick up from the people around them. That’s the sort of wonderful population one can only play with in a story like this. And we can tell so much about the world and its people from their reactions to the newcomers — this group of beings which is immediately suspected of being Up To Something, or might get mistreated as an exploitable resource, or led astray. It’s often said that the true measure of a society can be found in how it treats its animals — in the Dreaming we get to go one better and say look at how people treat their blanks…

As we shall eventually see, a lot of the arc’s ending – and a lot of next arc – revolves around themes of youth and inexperience. The blanks play a critical role in all of this.

Lu: In the conclusion to this story, whether it’s at the end of this arc or the end of the series, what do you hope to offer to readers through your team’s exploration of these themes of displacement and the way we treat the suffering—whether it be potential solutions or simply advice?

Spurrier: Always question, always empathise, never preach. That’s the goal.

Cool.

So he sacrificed characterization and established character personalities, along with plot just to tell American readers that Trump is bad and bigotry is bad. Why? Two thirds of us didn’t vote for Trump so why punish us this way?

I might have been able to handle the unsubtle message if the story was enjoyable and the characterization was consistent but poor Lucien being turned into someone who coldly uncreates Merv’s friends on the steps of the castle- Things like that bug me. And having Judge Gallows destroy Dreams in a worse and more permanent way doesn’t make that okay.

Frankly I’m tired of the “message.” I don’t like Trump. I don’t like what he does. I agree that irrational hate and reactionary politics is wrong. Most comic book readers do.

So why preach to us the morals we already heed? It seems we can’t read or watch anything today without the same message- a message that feels like a punishment for electing Trump and yet …we didn’t. He didn’t win the popular vote. Most of us (the entire country) voted against him. It’s the damn electoral college that got him in power. So why do we have to keep suffering through pop culture telling us how wrong we were for electing him? We …didn’t.

We already are standing against him as best we can. We NEED the escapism. Neil Gaiman once told a fascinating story about an elder cousin during world war 2 who defied the Nazis by telling a story (Gone with the Wind, I think) to her fellow prisoners. They needed that escapism, not preaching about why Hitler is bad.

We’re not as bad off as those poor women during World War 2. Not by a long shot. But we are (for the most part) unhappy with the current political climate. Reminders of it aren’t helping.

We need our escape. We can’t find it anywhere. Even last year’s season of American horror Story was one long political rant (American horror story: Cult). It only made a turn-around this year with American Horror Story: Apocalypse. We need our fantasies. Not rants about why we, as a people, suck and Merv is an asshole.

What we need is… Hope.

Comments are closed.