by Alex Dueben

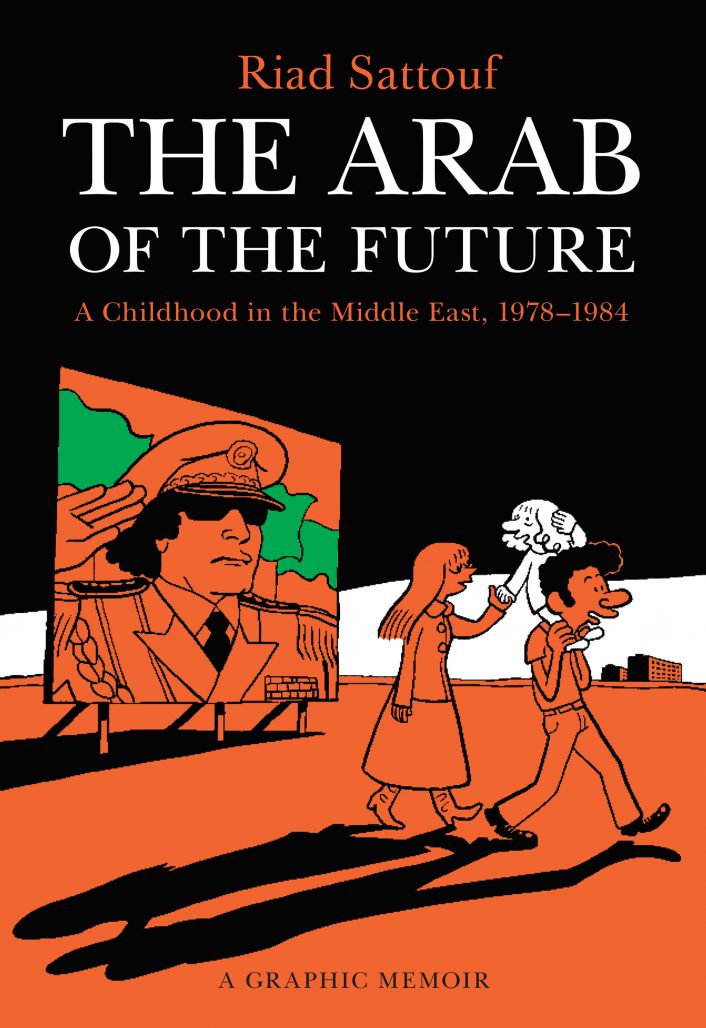

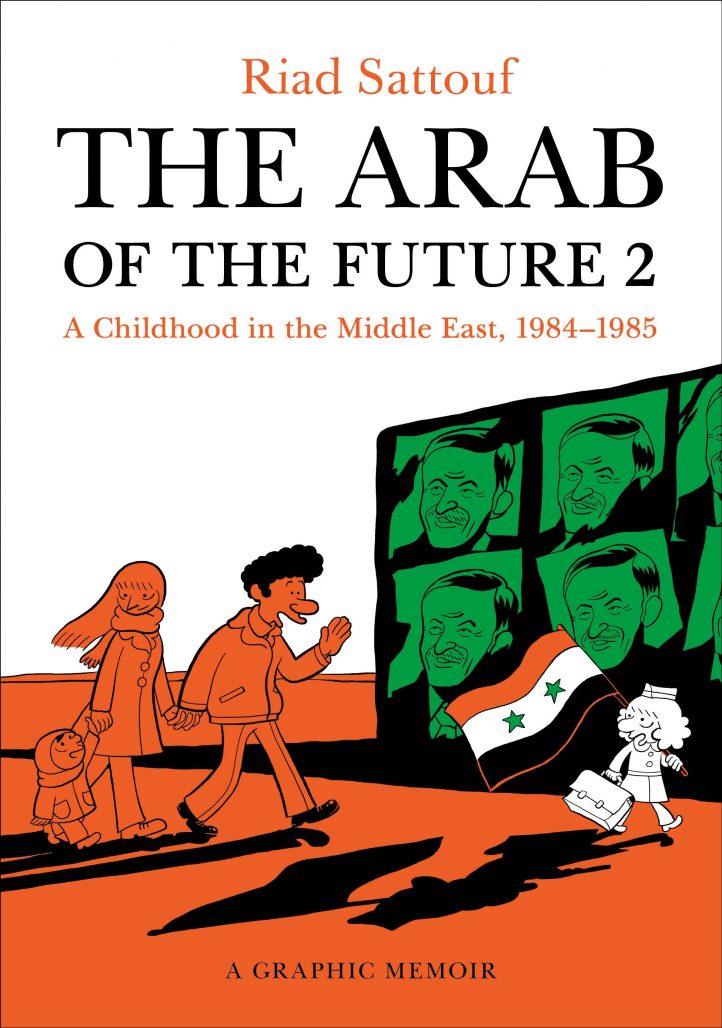

Sattouf was a significant figure in French comics before the series due his many other books including Les Pauvres Aventures de Jérémie, Retour au collège, Pipit Farlouse, and Pascal Brutal. He also wrote and directed the films The French Kissers and Jacky in the Kingdom of Women. For a decade he wrote a feature for Charlie Hebdo called La Vie secrète des jeunes, and in recent years has been making a weekly feature for the newspaper l’Obs. During a recent trip to the United States Sattouf sat down to talk about the second volume of the series, how it relates to his other work and why he likes to tell stories form the point of view of children.

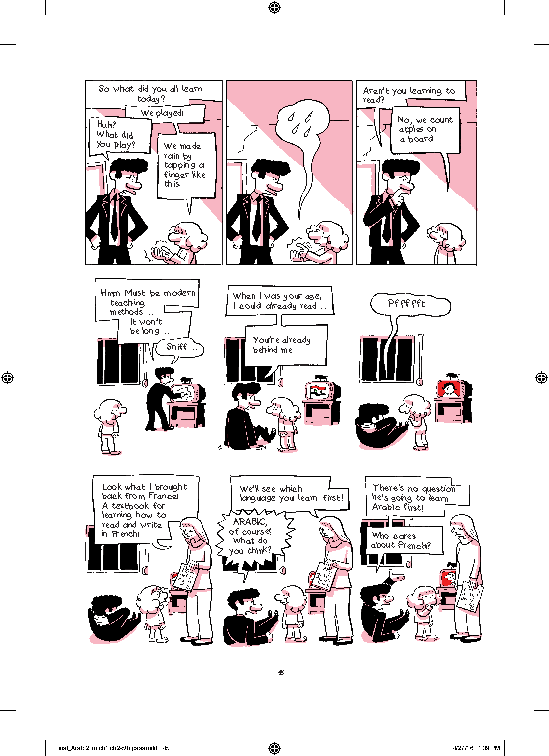

Sattouf: I like the point of view of children because it’s a point of view without judgement–or very few judgements. It’s a very innocent and naive point of view. I like to show the adult world from the child’s point of view because it reveals a lot of absurdity and a lot of paradox and craziness that when we are adults we don’t often realize.

Dueben: As a kid we don’t know any better and so we just accept everything.

Sattouf: Yes, we accept everything. In The Arab of the Future I show that as a child I admired my father. He was a far right Arab guy saying horrible things and thinking terrible things, but as a child you think it’s normal.

Dueben: Reading the books it’s clear that your mother occupied a unique position in Syria. I’ve seen from my time in the Middle East that Westerns, non-Muslim, non-Arab women do occupy outside of typical gender roles and expectations. Did you have a unique position of sorts because of that?

Sattouf: As a child, some of the other children were accepting–and some children were from my family–and a lot of children saw me as a stranger like from another planet. They were always telling me that maybe I was a Jew, maybe I was an Israeli, maybe I was a traitor. They were always asking me about religion. If I was a good Muslim. I had to prove every day that I wasn’t all those kinds of things that were different from them

In the case of my mother, nobody told her anything. She was free to be like she wanted to be. Because my father was considered somebody educated and he was always seen as a doctor, people respected his wife. It was quite a mystery for me at that time.

Dueben: Not to negate any of the anti-Semitism that they were taught, but I kept thinking that one reason they called you an Israeli or Jew was because they had a limited context for someone who wasn’t like them.

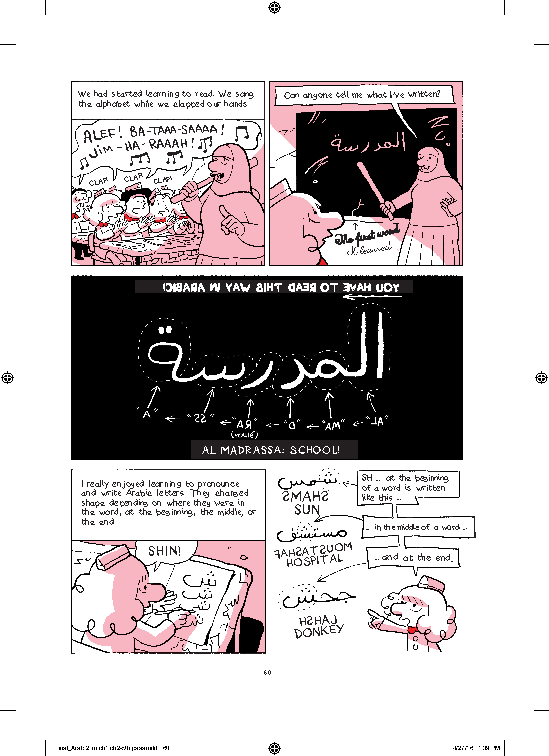

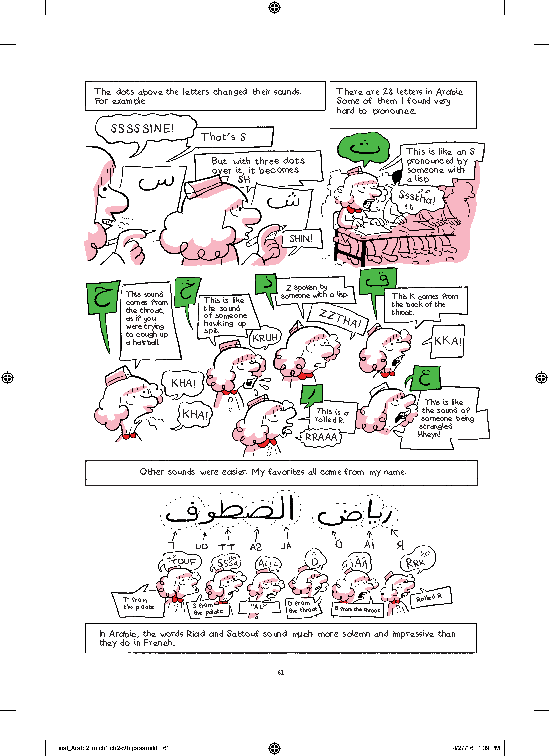

Sattouf: Yeah I think so, but also the Cold War was very vivid in their minds. It was very strange because they were living in a small village but they knew very clearly that Syria was an ally of the USSR and that France and Europe were with the United States and the United States was the enemy of the USSR and a great friend of Israel. So because I was from France, I was an Israeli. [laughs] It was really simple for them. It was children, but a lot of adults were thinking that also. I don’t know where they learned that. It was clear in their minds. I showed that there were anti-Semitic texts in the books we used in school to learn to read, but this was before we were going to school, so I don’t know. Maybe their parents?

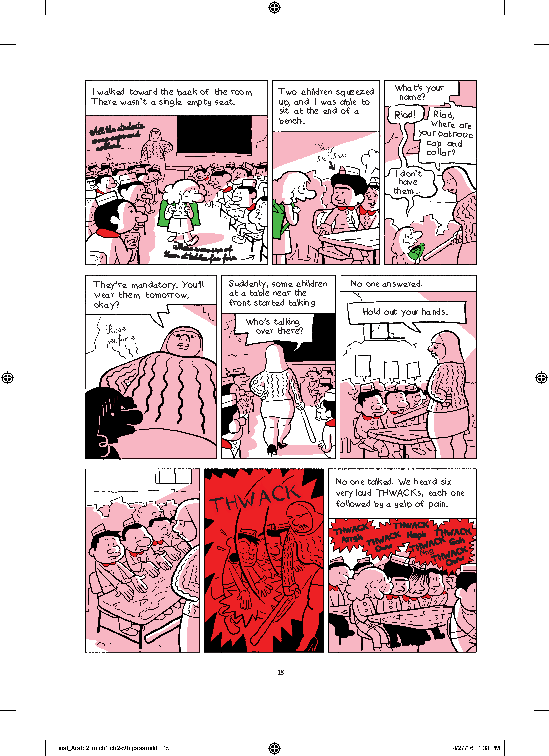

Dueben: Reading about what the teachers were like was a little terrifying.

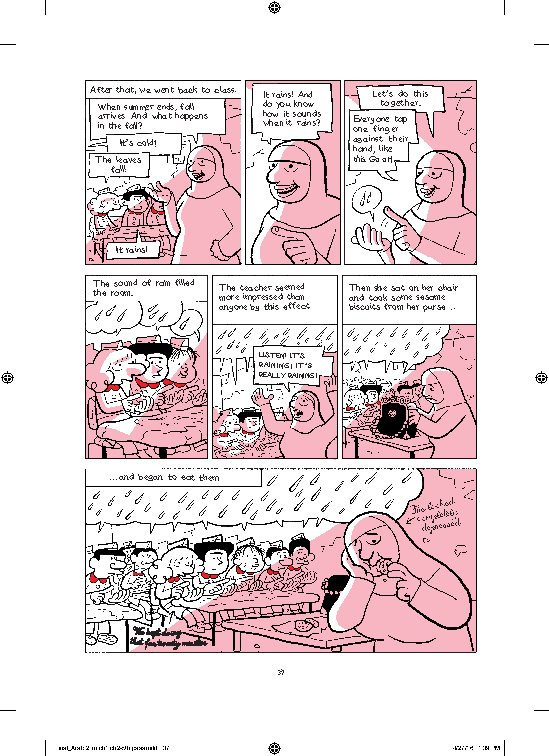

Sattouf: I wouldn’t say it was terrifying. At that time it was normal. [laughs] For me I thought it was like that for everyone on Earth. Later I discovered it was not like that. It was interesting to experience that. It was very violent in many ways but it’s interesting for what it says about human nature. You can learn to read and to write with very gentle and kind manners, but you can also can learn to read and write being beaten all day. The two systems work. It’s very strange.

Dueben: It was interesting to look at the differences between France and Syria that you were very conscious of even as a child.

Sattouf: It was very clear very early that there was not so much difference. It was only economic differences. For example in Syria the children hadn’t money. They were very poor, from peasant families. In France people had money, but it was very clear that sixty years ago, things in France were like it was in Syria. When my grandmother and the old people told me about their school, it was like in Syria. The teachers were hitting children the same way. Syria was backward in time, but it was quite close in many aspects also.

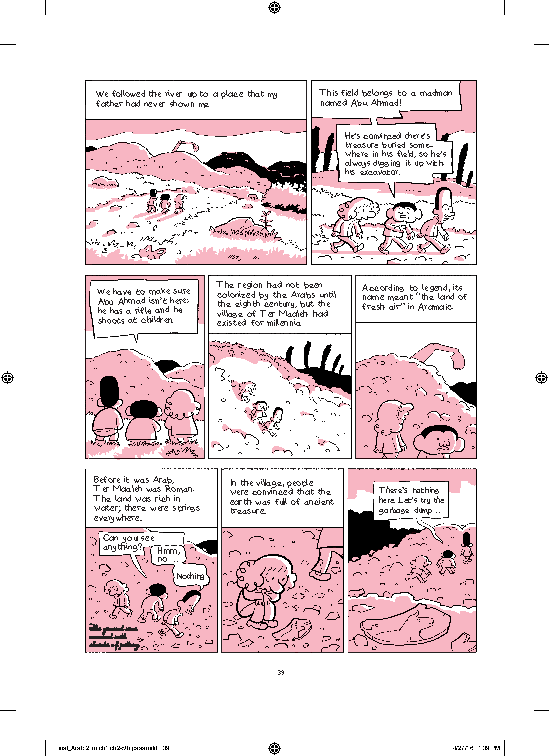

Dueben: When I meant differences, what stood out for me was that outside of school kids in Syria were left to their own devices.

Sattouf: Exactly. They were free to do what they wanted. It was very adventurous life. In France everybody was taking care of the children and they were afraid of them having an accident. In the village where we were living in Syria, it wasn’t like that. It was a very rural life, but I think it was the same in France at the beginning of the century. I meet old people and they’re always telling me, when I was young it was the same in France. If you look at the movie The 400 Blows, Francois Truffaut describes his school in France just before the second World War and it’s very close to the Syrian school I describe in my book. It’s a boy’s school and the teacher hits the children. It’s progress that makes things change. It’s not the cultural specificity, I think.

Dueben: I think so, and your grandmother lived and your mother grew up in Brittany which is a rural area and so you could see these similarities where if you were in Paris, for example, you wouldn’t have necessarily.

Sattouf: Yes exactly. It was a very poor region of France for a very long time. As I described in the first volume of The Arab of the Future, the neighbor of my grandmother was an old woman. This was in Brittany in France in the eighties and she had no electricity, no water. If you took her and her house and put her in the Middle ages, she would have lived without any problems. [laughs] It was very strange to see this way of life with my eyes. Her conditions were worse than the conditions in Syria. This is why I showed her in the books because it was very clear for me at the time also.

Dueben: You didn’t see going between Syria and France as a radical shift, you could see there were similarities from a young age.

Sattouf: Yes, but it was the end of a lot of those similarities. When my grandmother’s neighbor died, she disappeared with her world. Her house goes to her family and all her world disappeared completely and modernity came. She was the last of the ancient world. [laughs] It was very strange to see it go.

Dueben: I’m curious, when you started as a cartoonist, who were the creators you liked and read?

Sattouf: When I started I loved a lot of L’Association. One book that was very important for me was Livret de Phamille by Jean-Christophe Menu, one of the founders of the publishing house L’Association. It’s one of the first French autobiographical comic books published in France. It was really impressive for me because it told the story about his family and his marriage and his wife and his children. I discovered that comics could explore every subject and not only entertainment and science fiction and fantasy. I discovered another path of comics. I was a huge fan–I’m still a huge fan–of Richard Corben. Those were very important in my own private mythology. I love Chris Ware. For me he’s one of the gods of comics. His incredible pages with thousands of little drawings, powerfully written, I really admire his work.

When I want to concentrate, I think about Chris Ware at his drawing board, working all day, and I think okay, let’s follow his example. [laughs]

Dueben: When you were starting to think about The Arab of the Future, were there books you looked to besides the Menu one?

Sattouf: No. It was important for me to try to not be influenced by other cartoonists. I read Tintin, I read Chris Ware, I read Shigeru Mizuki. His Showa. It’s very difficult to say I’m influenced by Mizuki, or I’m influenced by Chris Ware. That’s not true. It’s impossible. They’re models you can think of for inspiration, but they’re too powerful to be direct influences.

Dueben: I know some people have criticized The Arab of the Future, arguing that the books reinforce negative stereotypes about Arabs and the Arab world.

Sattouf: It’s not really true that there is controversy. I think it’s more journalists looking for something to say about the book. I don’t know. I’m only telling stories in my own way of my own life. I’m sure a lot of people don’t like the way I draw my characters’ noses or their eyes or their expressions. You can read what you want in every drawing. I’m just telling my life. I don’t care what people think. I’m really happy to be well understood by the vast majority of readers. Some readers didn’t like it, but I invite them to read 50 Shades of Gray or something. There’s plenty of other books to read.

I’ve met a lot of my readers and I never met anybody who told me, oh what awful people. Of course I describe violent things, but what I’m describing is very human and common to a lot of cultures. Not only to this culture. For example I was in Brazil and I met readers who told me, when I was young it was exactly the same. The violence of the rural life is universal, I think. I’m just showing my own experience.

Dueben: People could cite your book Retoire au college, for example, and say some characters are a negative stereotype of a certain type of person, but you’re writing about individuals

Sattouf: Yes, of course. I’m telling what I’ve seen. It’s true I have a certain way of seeing things. I like to make fun of people and of what I see. This is my way of telling stories.

Dueben: In The Arab of the Future, you do explain what Syrian society was like and in talking about your father and what attracted him and others to people like Assad–the same thing that attracts people to Putin or Trump–the book does offer some understanding about how Syria functioned and how it could fall apart.

Sattouf: It’s difficult for me to say that because this was not the purpose of my book. I wanted to tell the story of my family, from the point of view of a child who is fascinated by his father who is fascinated by dictators and strong, powerful men. Of course this story could explain things, but that’s not the purpose of the book. I let the reader think for himself. Syria is a complex country. Before the war it was a modern country, but an extremely corrupt country. Like all the Arab countries. Like all countries. I think the fight against corruption is one of the main ways to bring progress and modernity. It’s very complicated to explain how those systems work just with one phrase or even one book. I just wanted to show the life in this small, sunny village at that time. Maybe it could shed some light a little bit on life in Syria, but it’s not a definitive way of understanding what is happening there. That is not my purpose.

Dueben: That is an important point to make. You’re not making a book to explain Syria or the Middle East.

Sattouf: I’m telling about life in the village of Ter Maaleh near Homs. I received a lot of messages by people from Algerian origin, from Tunisian origin, from Moroccan origin, telling me, it was the same when I was young in my village. They recognize things, but it’s also very different from one country to another. There are also people in France who recognize themselves in the rural life I describe in Syria. I’m just trying to describe the what I saw, my own experience, and I let the reader make his own theory about it. I’m not doing it for the purpose of explaining everything. I don’t like books that are too clear in what they express ideologically.

Dueben: You didn’t make the book with an ideological perspective. You resist reading books with an ideological purpose, as well?

Sattouf: As a reader I like books that have various points of view. I don’t like when the way the author thinks is too clear. For example when I do meetings in bookshops sometimes I meet people who tell me, oh your father what a horrible person, and then the guy just after him says to me, your father was a touching character with his weaknesses. This is what I like. I like to have two ways of interpreting things. I think that’s much more near to what life is. You can interpret things in many ways.

Dueben: That may be one reason why you like writing about children. Because they have less bias, the events they describe are more open for the reader to interpret.

Sattouf: Yeah, maybe that’s true

Dueben: The third book will be out shortly in France. How many volumes do you have planned?

Sattouf: I have five volumes planned.

Dueben: When does the fifth book end?

Sattouf: I won’t tell you! [laughs] I will keep it for the books. It’s like if I was telling you the end of Games of Thrones or Star Wars.

Dueben: Everyone’s going to die at the end of Game of Thrones. We all know this. I take your point, though. So you’re working on the final two volumes and still making your regular feature for The New Observer?

Sattouf: [laughs] Yes I’m still telling the story of Esther’s Notebook (Les cahiers d’Esther).

The PERSEPOLIS of Syria!

– “your book Retoire au college”

Tyop, that’s RETOUR AU COLLÈGE (“Back to Junior High”). Great graphic reportage.

– “The third book will be out shortly in France”

Came out in October, I guess this was a summer interview?

– “Sattouf: I have five volumes planned.”

Summer 2014 (Vol. 1), it was a trilogy. Summer 2015 (Vol. 2), he said four volumes. So now it’s at least five? Heh. (Not that I’m complaining! But its themes seemed patterned after Marcel Pagnol’s classic three-then-four-volume memoirs, so I wonder how more volumes will tweak it?)

Comments are closed.