by Alex Dueben

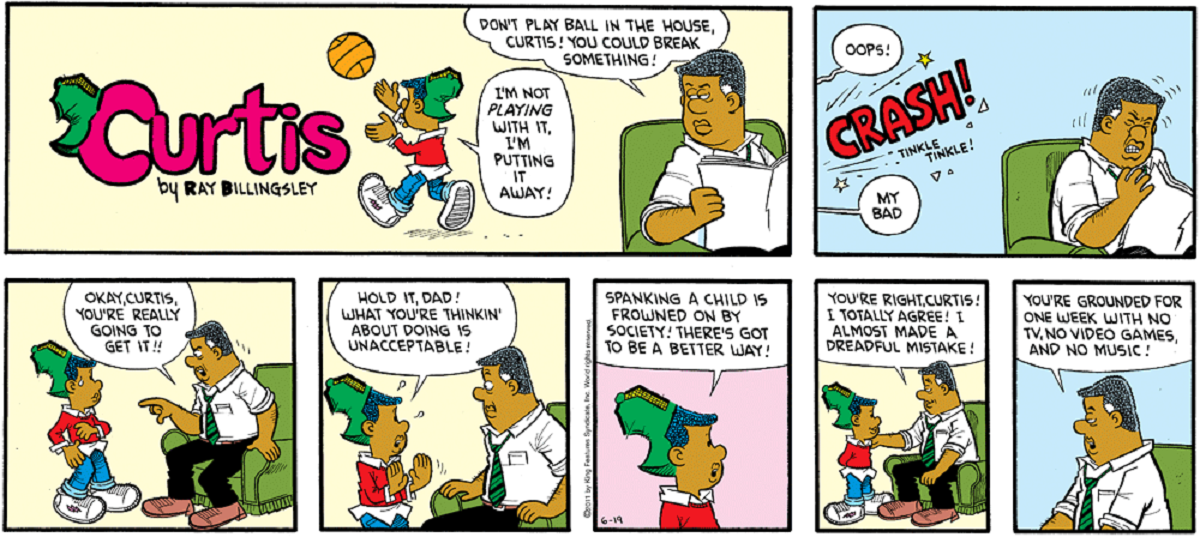

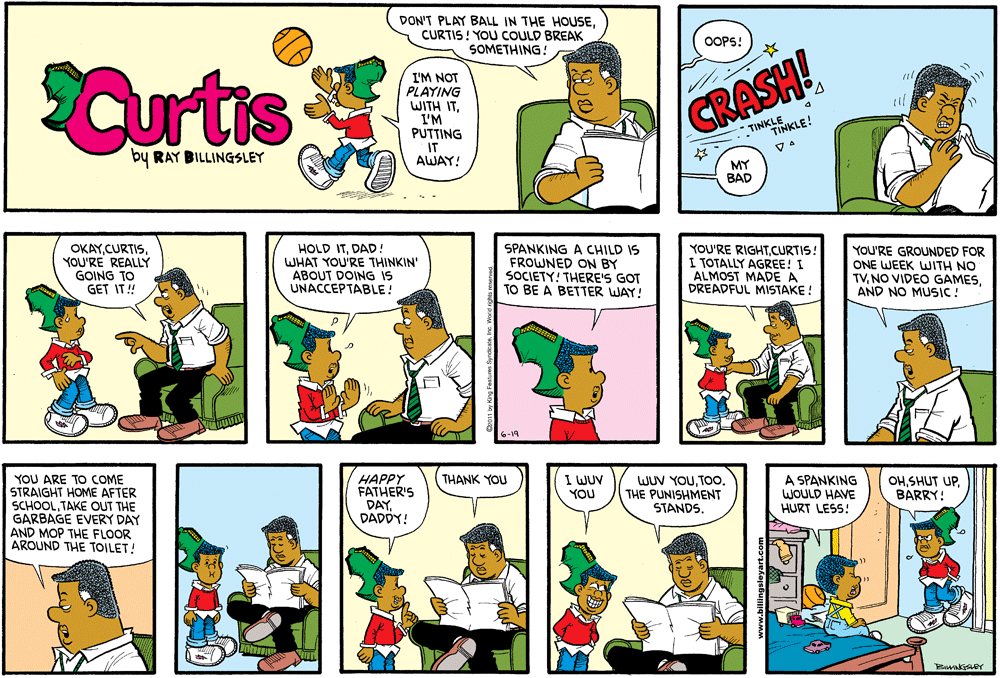

Ray Bilingsley started freelancing professionally when he was twelve years old. A graduate of the School of Visual Arts, where he studied under Will Eisner, Billingsley became the youngest syndicated cartoonist in the country when his first strip “Lookin’ Fine” was launched. Since 1988, he’s been writing and drawing “Curtis,” which is syndicated in hundreds of newspapers. What is most striking about the strip is how experimental that Billingsley continues to treat it with many different features that take over for a week or two, with the many characters and approaches used to tell stories.

The only strip that “Curtis” seems to resemble would have to be the classic “Li’l Abner,” which also regularly changed tone and approach for stories for a week or many weeks at a time. After so many years, “Curtis” reads and feels like no other strip in newspapers today. At its heart though it remains a story about family and about growing up. Though most aspects of the strip are either universal or utterly unique, Billingsley is open about many of the struggles that he faces in trying to find a larger audience for the strip, one of which is simply that it features an African-American family. He was kind enough to take time out of his busy schedule to sit down and talk about his career, Charles Schulz and Will Eisner, and trying to craft something unique and personal every day.

Alex Dueben: I grew up reading Curtis because it was in my hometown paper, The Hartford Courant, but I know that by the time the strip launched in 1988, you had been working as a cartoonist for a long time.

Ray Bilingsley: I literally grew up in this industry. I started off as a child selling my first work. The only job I ever had was a small stint at Disney and I left that to pursue my first comic strip. Curtis is actually my second one. The first one was called Lookin’ Fine and that premiered in 1980, so I’m a long long time vet of this industry.

Dueben: The story I heard was that you started freelancing as an artist when you were twelve.

Bilingsley: You hear a lot of artists saying that they were always drawing, that their family was behind them. Mine was a different story. I grew up under the rule of a very strict father. He didn’t think that a black kid or young adult could actually make a career – or even any money – from drawing cartoons, so he actively discouraged me from pursuing this. I didn’t have many friends, I was very introverted, and I spent most of my time drawing. My older brother and I shared a room – much like Curtis and Barry – and my brother used to draw fine art. I was a kid and I couldn’t compete with him so I started drawing cartoons. By the third grade I started getting some notice for these cartoons in school.

In the seventh grade my class was doing a holiday themed project outside of a hospital. To construct an eighteen foot tall aluminum can Christmas tree to tie in with recycling. I thought it was a dumb project so I slipped off to the side and I began drawing in a little pad that I had that I had started carrying around. I was approached by a woman who asked to see what I was doing, so I showed her and she asked if she could have it. I told her yes and she asked for my name and phone number and I gave it to her. I think that was a Thursday. That Monday she called me up. She was the editor of a magazine called Kids and she asked if I would come down and draw a couple of pictures to go along with an article. They liked it so much they hired me as a staff artist. Every day afterwards I had to show up for work at a magazine.

It’s funny. It began my whole transition to being isolated from other people. From that point on as I grew I couldn’t really play sports like other guys did because I couldn’t injure my hand. I had to worry about dealing with contracts at a very early age. It made me grow up very fast. Also when you see a lot of kids outside playing and you’d like to be there but you can’t because you have a deadline. I sacrificed a lot for the industry but it was an industry that I really loved because they welcomed me. It was during a time when there was a lot of strife in the country. I started in the industry in 1969 so we know what was going on. [laughs] The way my dad felt towards me, I was never close to him. I also didn’t like him for most of my life. After he passed, we were going through boxes that he had and we came across all these articles that had been written about me and drawings from magazines I did that he had collected. He had kept up with it all the time but he never let me know so I guess he approved. I never found out.

Dueben: That’s interesting because of course the dad in “Curtis” is a man with a job he doesn’t like and he’s gruff, but he’s also very affectionate and takes time with Curtis and Barry.

Bilingsley: I’ve been asked this question before – if I had the same sort of relationship with my father. I always told them, what I’m drawing is the relationship I wish I would have had with my father. Once my dad came home from work, all fun was over. The kids retreated to their rooms. We didn’t speak much. I think a lot of that has colored the way I am as an adult because I’m a very quiet person. A lot of people in the industry know me, but when you really ask them, they don’t know that much about me. That’s because I’d been taught not to talk about myself much. I don’t even do interviews that much. My moms was religious and she said to talk about oneself or one’s accomplishments is prideful in the eyes of God. So I turn out to be this little badass. [laughs]

Dueben: I’m sure it was strange and isolating as a teenager, but then you went to the School of Visual Arts where you were surrounded by other artists.

Bilingsley: It was very competitive, but there was camaraderie. Everyone loved what everyone else was doing. We were all trying to help each other when we were going out on interviews or looking at portfolios. There were a few of us who used to get together for these all night jam sessions – almost like a bullpen. I went to the High School of Music and Art so every student there was creative and that really helped. Where I grew up, nobody that I knew was into the creative arts like I was. There you go again – isolation. I had actually won a full four year scholarship to the School for Visual Arts, which really helped because I was actually on my own. That goes back to my father and I really not getting along. I couldn’t wait to get out. I had money saved up from my freelancing jobs so I was able to move out on my own. In those days people were more trusting. All they worried about was if you could pay the rent. There were no credit checks or things like that. You walked down the street and there’s a sign on the building saying apartment for rent, you went and rented it. The School of Visual Arts was not only a good place for me to be in terms of other people, we had a really nice job placement department there and I was there almost daily checking out different freelance jobs. At that point I was basically surviving on freelance so when I was working on one job I was going to an interview for another job and probably at the same time being owed for a job I did right before. In those days way before computers, the market was very lucrative. There were so many magazines and so many of them were situated in New York so you could just go there. Well, you couldn’t just drop in – you made an appointment, but you showed up at the office. By that time I had a reputation around New York for being this kid artist so it was like a novelty to them and I got a lot of jobs that way because I was so young.

Dueben: One teacher you had at SVA was the late great Will Eisner. This would have been in the seventies before A Contract with God came out and his career revival that followed. What was he like as a teacher?

Bilingsley: Will was gruff. He wasn’t a teacher that played around. We’d be sitting in the classroom talking and when he came in, everybody got quiet. He wouldn’t say a word. He would walk to the front of the class to his desk and sit down. He would start his lesson and he didn’t care if you paid attention or not. As he would say, he already got paid. He said, you can play around, you can not be serious, I don’t care. I’m here to teach the people who want to learn. He actually knew a lot of the work I had done beforehand. The thing about Will, I don’t know if he was playing with me or not, but he was not impressed. He was always picking on me saying, well can’t you do anything else? Can’t you draw something else? It was a challenge to me. A lot of the students would transfer out of his class because he was too hard. I took it as a challenge. All I wanted to do was make the man smile. To get his nod of approval. So whatever he told me to do, I attempted to do the best I could. I would bring homework assignments up to him and he would take out his ink bottle and his brush and he would work directly on what I had done to improve it. He would show me what he had done and I would say, god, that’s one hundred per cent better.

I credit him for something I do in my strip now, a superhero called Super Captain Coolman. Will used to tell me about drawing in different styles and going beyond my comfort zone and experimenting. He gave me the belief that cartooning is art and every now and then, you should experiment. I don’t really see many people doing that. They don’t really get out of their comfort zone. Every now and then I like to do different things and work on different artwork that may not even look like I drew it or wrote it. Those are the things that he drummed into me. I was a kid that took a lot of advice from older, established people because I knew that I didn’t know everything. I would take what people would tell me and use it to my advantage. From Disney I got a real strong work ethic because they worked your tail off. You had to draw all day long then go to mandatory art school afterwards. Then when I came home I worked on my own stuff. Charles Schulz told me to find something that is uniquely mine that no one else can touch. With Will it was experiment and push the boundaries and see what I can get away with.

I remember the first contract I got for Lookin’ Fine, I rushed in and said, Will, I got the contract! He immediately snatched it out of my hands and started reading it and said, get your lawyer and make sure you get this and that. I said, okay. I was already used to contracts by this time. I already knew all about the double talk and everything like that. When I was doing “Lookin’ Fine,” I was the youngest syndicated cartoonist in the nation. Will helped with that. I’ve always had people who look out for me who were well established. I think it’s because I was so young they either saw a bit of them in me, or they just thought it was a hoot. [laughs] That this kid is actually doing this stuff. Mort Walker and some of the other guys used to tease me by always calling me “kid” because I was always the youngest one around. Some of the ones who knew me from when back then still call me “the kid.” [laughs]

Dueben: When you were talking about experimenting I thought of all the Kwanzaa strips which really stand out both in relation to the rest of the year but also to what we see elsewhere on the comics page because you draw and write those strips in a different style.

Bilingsley: Those are a hassle to do because of the confines of the strip. It’s so small I really have to work on each panel to make it look aesthetically pleasing. I’ve noticed that over the years the younger generation aren’t really into the stories as much. I’m not doing the Kwanzaa stories every year like I used to. I want them to be more special now so maybe one year I’ll do them and then the next year I’ll skip. People change, readers change, the times change. You don’t want to lose readers and you also want to get new ones. When you do get a new one you want to keep them. Some of these Kwanzaa stories really appeal to the older set but you also want readers who may not want that. That is probably why a lot of people don’t leave their comfort zone. When you’ve got something going, you just keep doing it. But I would get bored if I didn’t stretch out every now and then. I think when you look at people’s work, you can tell if they’ve had a bad day or if they’re bored and are just putting it out to meet the deadline. I never wanted my work to reflect that.

Dueben: You didn’t do a Kwanzaa series last year.

Bilingsley: I did have an idea but it didn’t really gel out the way I wanted it to. The story has to be perfect for me to work on it. I’m a stickler for it being the best it can be. I’m so hard on myself that usually when things are printed, I don’t even look at it because I can always see something that I could have done differently. I could have worded something a little differently, I could have used a different angle, a different expression. So once it’s out there I don’t bother with it anymore.

Dueben: I’ve read a ton of your strips to prepare this and thinking about similar strips, the ways you try different approaches, and the strip I think Curtis most resembles is Li’l Abner.

Bilingsley: That’s my favorite strip!

Dueben: Al Capp has a very different reputation today than he did then, but the strip was parody and slapstick and it could be thoughtful and then have other unrelated pieces. It really was a world.

Bilingsley: I think his was one of the greatest strips out there that didn’t get the just due that it should have. The art was magnificent. I don’t know why it didn’t get the same sort of play – maybe because they were portrayed as country bumpkins? It seems like nowadays there’s more attention towards art that isn’t so elaborate. It seems like that’s where people’s tastes are headed for some reason. I wanted Curtis to be its own world. He’s in the city, granted, but it can be any city. It’s not New York, it’s not Philly, it’s not Washington, it’s his own city. That’s what happened with most of the great strips. Peanuts had its own world. I thought Al Capp was one of the best. I wish I could draw as good as he could. He’s still tops to me, although I have a different style.

Dueben: It is its own place. And it changed over time, as the world you created has. I remember one of the older features in the strip that you dropped was the music store which kept changing names and locations because the parents would burn it down.

Bilingsley: Well, topics have to come and go because the times change. When I was doing that, rap was still banned in most places and people didn’t want to hear about it. Curtis and his cool friends had to go and search these things out. Curtis knew exactly where the music store was whereas Barry never knew because Barry’s not old enough to be cool yet. Each time it was in a new location under a new name because parents would find it and burn it down. It could be the “Mike Tyson Linguistic School” or something outrageous. What happened was, rap because mainstream. It wasn’t so deadly anymore and Curtis didn’t have to hide it. That was something that had to go.

I’ve had quite a few topics that I really liked doing that met its fate because of time. If I’m not careful, Gunk may be the next one. I notice that younger people are not so accepting of this sort of fantasy anymore. He came from a different place and he was the son of the ruler. I started getting complaints about him. Why does the token white guy have to look like this? Well, it’s not the way he looks, he’s just different. He’s not American. Does he have legal papers? Um, this is a comic strip. It’s not real. He doesn’t have to have papers. Things just change. I used to have and had a good deal of fun with Curtis taking a phone call and Barry listening in on the extension. What happened? Cell phones. So there was no more need for extensions and those sort of gags died out.

Dueben: And Curtis’ dad used to be a heavy smoker and you had him quit and really dealt with smoking head-on.

Bilingsley: He may do it sporadically now but it’s not as bad as it used to be. There was a time in New York that people smoked everywhere. You went to the movies and you saw the movie through a cloud of smoke. It was things like that which prompted me to write that stuff and that was during a time before it was popular to crab about it. There were still characters in the comic strips that were heavy smokers. I started writing about it and all of a sudden, it caught on and everybody stopped smoking. Because of these strips, I was working with the Lung Association. They gave me an award for all this anti-smoking work I had done. It took me by surprise because I was just letting my creative mind go and that’s where it took me.

Dueben: You’ve been doing Curtis for over 28 years now and we’ve been talking about what’s changed in the strip, but is there something that’s really changed for you in terms of your work or making the strip?

Bilingsley: I’ve come to accept a lot of things about the industry and not look at them through rose colored glasses. A lot of things that I had expected to happen that never did happen I just came to accept because there wasn’t much that I could do. There’s more of a seriousness about me. I used to be very giddy and almost child-like about this whole industry. I found out that I have to take this all very, very seriously because it’s a very serious business despite what outsiders see. People think that it’s just fun and games all the time and it truly is not. It’s really a dog eat dog industry, a cutthroat cold industry. It took years to get me to actually realize that. I was having fun most of the time – until a lot of thing I was going after didn’t pan out. Despite all the accolades, the awards, the years I’ve been doing this, I’m still finding that I have to prove myself to people who haven’t even been in the business half the time I have.

That has been the real change. And just juggling life and work has been different. Life is a lot different for me now than when I was much younger. I could sit up all night when I was young and I don’t do that anymore. I’m much more cautious and careful with what I do. I wanted to make more of a lasting impact. When I finally do go to meet my maker, I want to leave behind work that is lasting. I want to be still spoken about–like Will, like Al Capp. I want to know that I have inspired some people and I know it’s only to be done through hard work. My strip is held up to different standards than other strips. Right away people are careful because they say, oh a little African-American kid. Is this going to be threatening? Is this something my child should see? There are stigmas attached to it before people even start reading it. Then when they start looking at it they go, it’s pretty good, I like this stuff. That was quite a learning process for me.

Dueben: When you were saying that I kept thinking about how there should be a shelf of Curtis books, which is probably more important today than ever just because of the state of newspapers as a way to get the strip out there.

Bilingsley: I can’t get mainstream publishing to take them on. I’ve gotten so many rejections. Mind you, it’s not just me. It’s the other black cartoonists as well. They’re not printing any of us. I can’t figure it out because some of the titles that they print, that are in bookstores, have less clients than I do, and yet they still feel that they’d be wasting their time trying to do mine. Mind you some of the work that I have seen put out there, I was never really a fan of in the first place, but for whatever reason these book publishers think they’re good so they put them out. Mind you, if you put out enough books by someone who’s doing bad art, people will take it because that’s what’s being offered. Myself and other black cartoonists were not offered the same opportunities as our white colleagues. We are not. The Hispanic fellows get it even less. The women in this industry get a hard hand at it too. We have some talented women cartoonists out there, but they don’t get the breaks. That’s one of the hard facts about this industry.

Dueben: You still believe what Schulz talked about, that your job is to get up every day and draw every line in every strip. That’s the one thing you can control.

Bilingsley: Schulz was another one of those adoptive parents that I used to have. I would latch onto the older cartoonists and they became family. Schulz used to always tell me, don’t do this work unless you always do the best every day. That’s why I didn’t do a Kwanzaa story this year. Never put it out unless you’re one hundred per cent into it. If you do that, somebody will notice. Somebody will notice that your strip is standing out because you take that extra time to do it. Schulz used to rag on me. He used to walk up to me and say, “Hi Roy,” or “Hi Craig” and he would start beaming this big smile. [laughs] In the strip I have Gunther, who never calls Curtis by his correct name. That is something Schulz and I had in common. His father was a barber and my grandfather was a barber. He used to go down to meet his father and walk him home. I used to meet my grandfather and walk him home. It’s funny. It wasn’t like he was a father figure, he was more like big brother. We would talk on the phone and a lot of time not even talk about the industry. I would come to him with a personal problem and he would give me advice – I guess, like a father figure. [laughs] He was just a wonderful fellow. There were times I used to wonder why I had this closeness with the number one cartoonist of all time. Then I got to the point where I just accepted it. We were just buddies. I went to his home and he showed me to his study I looked around and said, this looks like the place of a modestly successful artist. He bust out laughing. [laughs]

I asked him once, what’s it like to be you? To get up every day and see your characters on everything from books to toilet paper? He said, it’s an illusion. You’ve got to work. He enjoyed the fame, but he was also a very quiet, disciplined person. It’s not like he was looking for fame, this is something he liked to do. He said, fame doesn’t change anything. It doesn’t keep your hair from going gray. It’s what other people put on you. You’re still the same person. People will stand and look at him and couldn’t even speak but he said, all they have to do is say hello. I was in the industry so long, that’s the way I was with everybody. I had no fear in coming up and just talking to anyone no matter how big they were. I think that’s another reason I became friends with a lot of the giants. I just treated them like regular people and a lot of them, that’s all they want.

Dueben: So what are you working on now? How far ahead do you work?

Bilingsley: I’m supposed to be six weeks ahead but I think I’m a week behind. I’m dealing with an aging mother and I have to go back and forth to New York to see her and make sure everything is all right and keep the family together. I’m still working on the strip. I have never given up the idea of having something animated. I’ve worked on a script and I’m reworking that. I have another idea that I’d like to present which is completely different than Curtis. So I’m working on a movie idea, working on an animated script, working on the strip. I’m thinking about a new series of books. We’ll see what happens. I’m always busy.

Curtis was always one of my favorite strips. Great interview!

Love his relationship with Charles Schulz and their take on fame.

Ugh, I haven’t thought about “Curtis” in years, not since my local newspaper dropped it back in 2007. To me, “Curtis” was basically a comic strip justification for why we still need to spank children when they misbehave.

Talk about an unlikeable protagonist.

Comments are closed.