In last week’s interview with Paula Knight, author of the graphic memoir The Facts of Life, we dove into popular cultures remaining difficulties with discussing fertility and the decision to have or not have a child. We also looked at identity and how society still tends to place the value of a person on what is or isn’t happening with their uterus. Today we venture in another direction, into the wilds of motherhood and infancy itself.

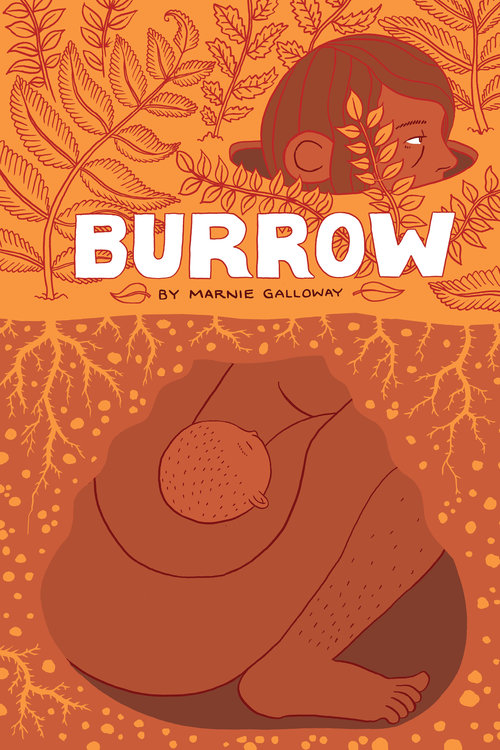

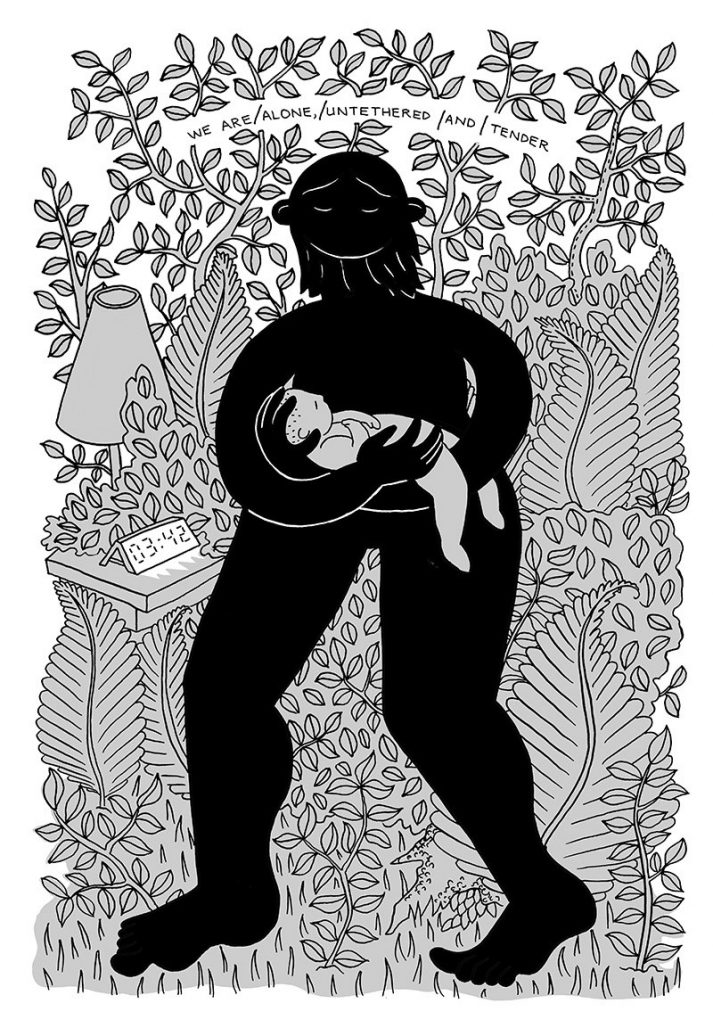

Marnie Galloway’s Burrow was published by Mutha Magazine back in October 2017, where I came across it. It is a beautiful meditation on the first feral weeks and months of motherhood. Raw, tender and poetic, Burrow captures the tension of new motherhood.

Creating

Cartoonist Marnie Galloway lives in Chicago but is originally from the Austin area. As a former Chicago area resident myself, I began our interview by asking her what it’s like to be living and creating in a city of over six million people, especially in our current political climate.

Galloway: “This isn’t about Chicago in particular, but about being an American making art right now: I think we’re going to be reckoning with what it means to make art at this particular cultural and political moment for a long time. I’ve oscillated between depression and fury and hopelessness in the face of the destructive, dehumanizing rhetoric and policies of the Trump administration. Fellow Chicago cartoonist & genius/friend Anya Davidson tweeted a while back something to the effect of “making art for the sake of art right now feels like prayer,” and I think about that all the time. What is the use of art? What is the use of prayer? Neither do the work of changing the world outside us—that requires sweat and community-building and organized strategy—but they hold the potential to build up our interior selves, provide structures for self-reflection, for meaning-making, for humanizing ourselves and others. They replenish empty wells and give hope; making art is in itself an act of hope. That is critical work right now, more than ever. At least that’s what I tell myself as I return to my drafting table every day.”

Galloway served as the former organizer of the Chicago Alternative Comic Expo from 2013-2016, she spoke a bit more about the creative vibe of the city.

Galloway: “Chicago has been my home for the past decade, and if I have any say in the matter I’m going to live a long life making comics here and die in this house, in this neighborhood. I do all of my work from my home studio, and I’m the mother of a young toddler—I’m not the most in-touch person to ask about what it’s like to work in the city today!”

Galloway: “That said, every year I look forward to CAKE, of course, as well as Chicago Zine Fest and the brand-new Chicago Art Book Fair; and several times a year there are innovative, dynamic performative readings by cartoonists at Zine Not Dead and Two Cookie Minimum. Chicago has long been a welcoming home to cartoonists, from the underground comix and imagists of the 60s onward, which I’ve always thought is interesting. Chicago is a big enough city to sustain niche arts communities, and affordable enough (relative to other major American cities) to make living here a sustainable proposition; add to that the School of the Art Institute and other local arts colleges churning out young artists with new ideas to keep the energy from stagnating, plus no obvious industry to gobble up that talent (like illustration in NYC or animation in LA), and you’ve got a recipe for a really exceptional and innovative comics art world.”

Burrow begins with a sentence and a thought. The comic builds slowly at first and then the pace quickens and the panels become more ornate, crowded with patterns, thoughts, and words. The comic follows the main character Isha as she navigates two selves, the one she new before becoming a mother and the one she is attempting to navigate now. The comic was partially inspired by the scientific readings Galloway came across during some casual reading. Galloway says she recalls reading the article about trees sleeping during an early morning feeding of her son.

Galloway: “I was looking at twitter on my phone in the dark—I think it was 3am?–and I saw a headline about trees sleeping from a science journalist I follow. I read the article and started crying (again, extremely sleep deprived): the image of a tree drooping in the darkness felt in-my-bones familiar to bending over in the dark to return my son to his crib. I knew I had a foothold on a new idea by that visceral reaction.”

Galloway: “I think about death all the time (I’M A LOT OF FUN AT PARTIES), but it was a borderline obsession when I was pregnant. I was convinced through my pregnancy that one of us, me or my son, wouldn’t survive birth. I had recently learned about the deathwatch beetle, a kind of beetle that eats rotten wood and makes a ticking knock sound on quiet summer nights; they earned the creepy name through association with keeping vigil overnight by the dying or the dead, and hearing the beetles tick in the rafters. Connecting my sleepless body with the sleeping tree, the eerie surprise that both my son and I lived, and this bad-omen beetle that eats rotten wood all felt of a piece. I’m horrible at writing on a deadline because most of my comics are written like this, piecemeal, hunting for strands that feel true when woven together rather than making the strands myself.”

On Identity Shifts

Ayres: The line “I am alone between two worlds” resonates deeply. Do you think people appreciate that feeling of isolation that comes with motherhood, is it something people talk about enough, too much? Basically, I’d love to know your thoughts on your shift in identity, how it felt for you then, and how you feel about it now.”

Galloway: “Isolation is exactly the right word to describe (at least my experience of) new motherhood, but not in the way I hear people talk about it. I knew well enough from seeing friends and family suffer through social isolation in early years of parenthood, and plenty of cliched representations of this play out in pop culture. Wanting to avoid that, I reached out so much to friends in the first year of my son’s life that I built much deeper and tighter connections with my community than I had before he was born. I’m lucky to have friends with flexible work schedules (freelancers and artists and grad students) who would spend days with me, and other friends who would visit for dinner or weekend adventures. He is recently in daycare, but for the first 18 months of his life it was just me and him and this open-door cycle of friends coming through. I am deeply grateful for my community who were unfazed by my new schedule limitations as a parent, and who welcomed my son into their own lives with open arms.”

Galloway: “But that’s not the isolation I was interested in addressing in Burrow. Birth, my own abnormally difficult physical recovery from birth, and the wilds of infant care made me feel like an island, my son and I as one unit apart from the world. People sailed past and threw supplies on my shores, but it was a profoundly solitary experience. I wasn’t expecting to be surrounded by people and still feel that way. My (unimaginably wonderful) husband was there for every minute, but he wasn’t recovering from birth, he wasn’t learning how to breastfeed, he wasn’t dealing with the waves and crashes of hormones and the joy and grief and relief that comes with holding in my arms a wriggling baby that had recently been wriggling on the other side of my skin.”

Personally, one of the most difficult components of contemplating motherhood has been my fear of a major shift in identity. I hardly feel like I know who I am now, to think about wrapping myself in the blanket of infancy sparks a fear of me that is difficult to convey. It’s why Galloway’s comments about her identity changes were especially prescient to me.

Galloway: “Parenthood has changed my schedule, and my body, and has exponentially grown the amount of love I feel in a given day, but it hasn’t changed who I am or what I aspire to accomplish as an artist. If anything, this experience helped me doubled down on what I know about myself. My mom calls times of hardship “FGOs”–fucking growth opportunities. They suck and are really hard, but you can come out the other side stronger. Pregnancy and birth and infant care are a marathon of FGOs; my identity didn’t change, my core self didn’t change, but they were tested by sleep deprivation and depression and a new kind of love that’s like seeing a new color. I’ve got more resolve than before, more confidence, a more solid core, even if my belly is decidedly softer.”

Patterns

I found myself compelled by Galloway’s use of patterning throughout Burrow. It’s subtle and creeps in until it partially obscures and overtakes. Galloway is known for her ornate use of patterns, in particular in her 2016 release of In the Sounds and the Seas. I asked her to reflect on her process and use of patterns in Burrow.

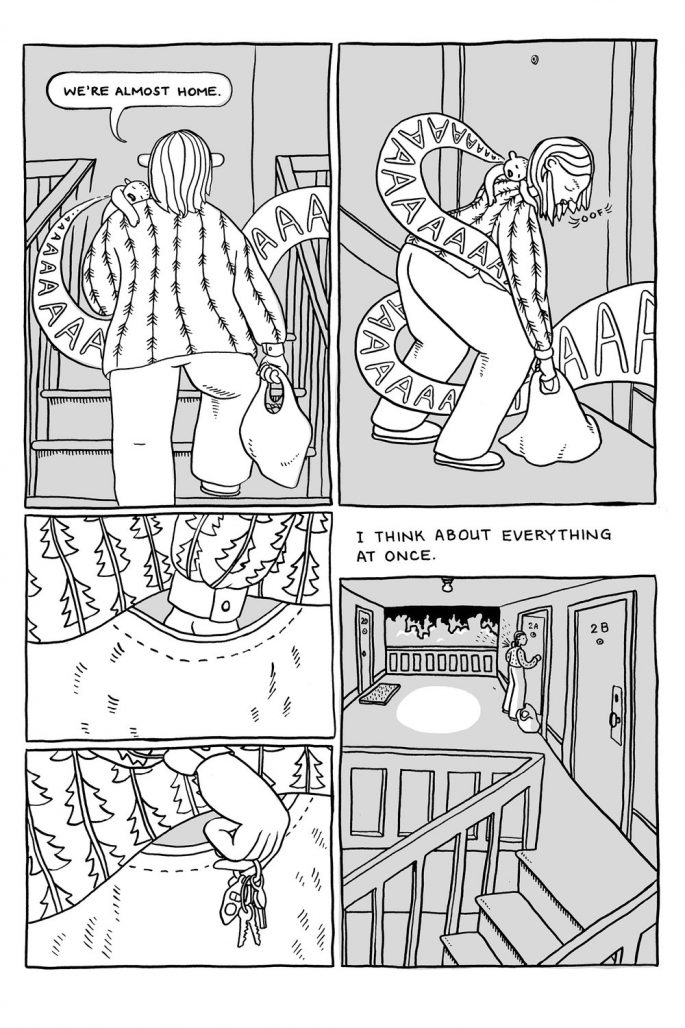

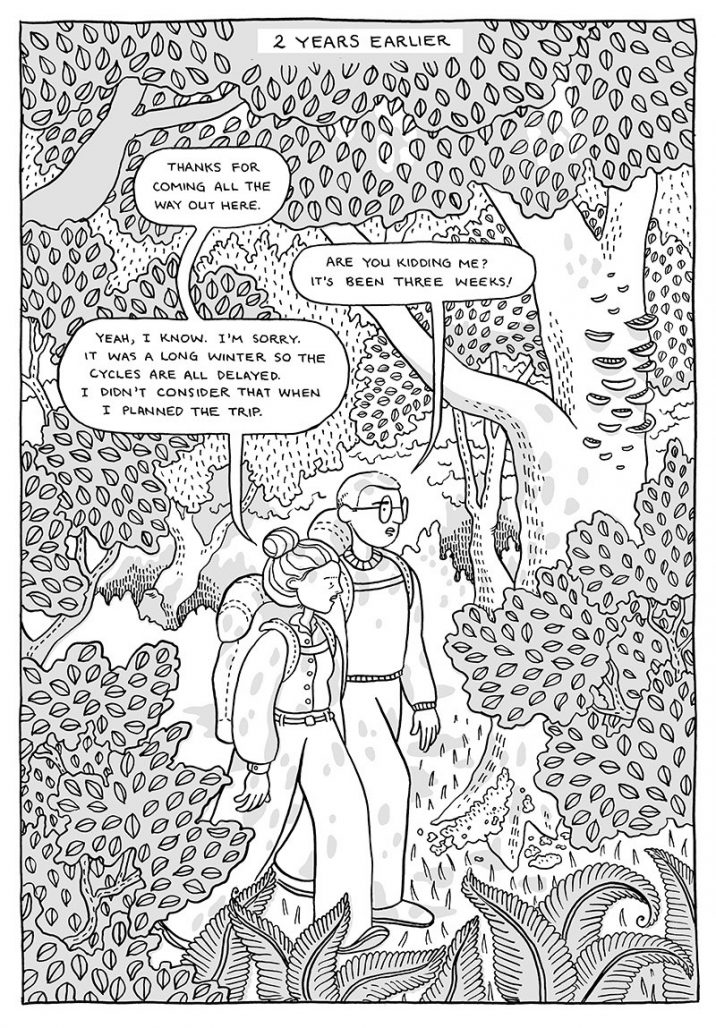

Galloway: “I felt like I was so restrained in Burrow! My last book, In the Sounds and Seas, had pretty obsessively patterned sequences, and I was trying to loosen up a little here. So, Burrow is divided roughly in three parts: the protagonist, Isha, putting away groceries and putting her infant to bed; 2 years before, when she was doing graduate field work in the woods, walking with presumably her partner, showing an unhealthy dynamic that suggests why he isn’t in the picture current day; and a half-asleep sequence back in the present, where she is reconciling those two parts of her life into a new self. For the third part, I cut and pasted words from the first two parts to create new meaning, to reflect the collaged self the protagonist is making.”

Galloway: “Visually, I wanted the first two parts to have very different visual textures so that the building of the patterns in the third part, amalgamating elements from the present and past, would be visually interesting. I didn’t pull directly from these cartoonists for Burrow—stylistically and thematically they’re really different from me and from one another–but I reread Sammy Harkham, Genevieve Castre, Ethan Rilly and Eleanor Davis comics before penciling this one. They’re all artists I admire, whose work I look to a lot for clarity in storytelling, deep wells of empathy and genius-level cartooning.”

I’ve read Burrow numerous times and it continues to find new ways of touching me, of moving me. It invites the reader to get in, get lost, lose themselves and perhaps find something else in its stead. It’s a raw and emotional journey into the forest of motherhood.

Burrow is for sale on Galloway’s website.

The comic is also available for free on Mutha Magazine who recently serialized the comic:

Burrow: Part I

Burrow: Part II

Burrow: Part III