Mainstream comics aren’t exactly known for their stellar depictions of parenthood, maternity, fertility or pregnancy. The pregnant superhero is treated as something to be maligned, a grotesque and monstrous object. The experience of conception and pregnancy is rarely the locus of attention in comics. If you venture into the world of indie and webcomics however, you’ll find a much more nuanced view of life and the decision to bring (or not) bring another being into existence.

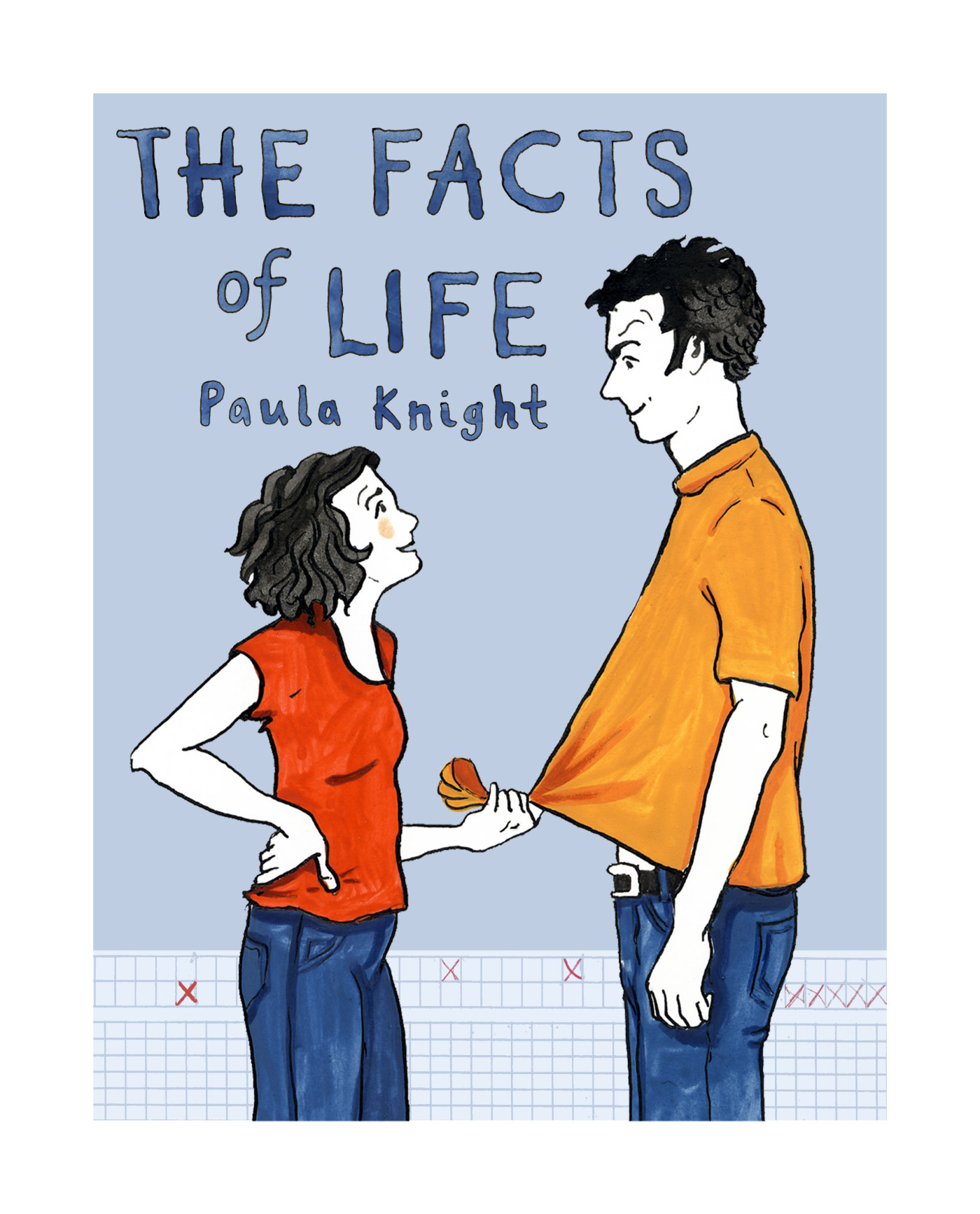

On the hunt for depictions of motherhood and fertility that didn’t feat neatly into a Hallmark-card-like-illusion, I came across the work of Paula Knight (The Facts of Life) and Marnie Galloway (Burrow). Both write beautifully about their experience of being a person either trying to conceive in Knight’s case, or those first frenzied months of an infants life in Galloway’s. I reached out to both and asked them to tell me how they came to write about their experiences and what they think of societies expectations and perceptions on the decision to become (or not become) a parent.

The Inevitability Factor

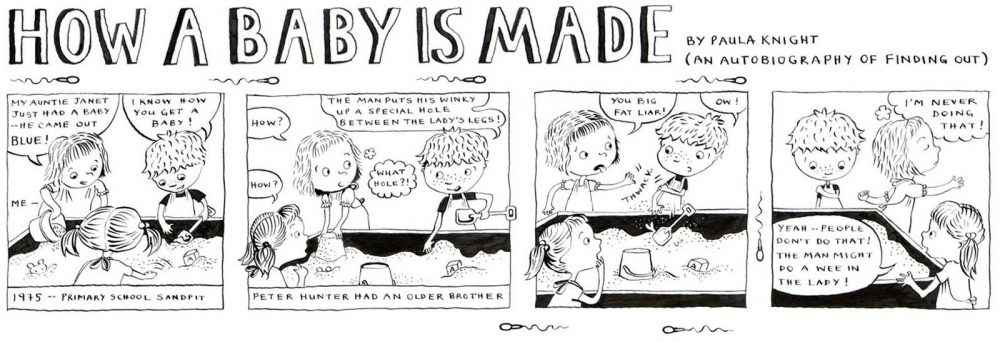

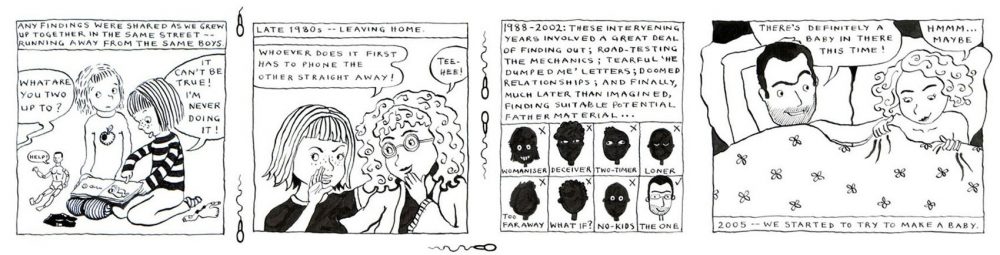

Ten years ago Paula Knight drew a strip called How a Baby is Made and posted it on the website DeviantArt. It would become the germ of her graphic memoir The Facts of Life, recently published by Penn State University Press. Knight grew up in Northeast England in the 1970s and it is around this time her graphic novel begins. Best friends Polly and April sit in trees talking about sex, boys, life and what their families might look like one day. The novel shows how the expectation of motherhood is placed into the lives of women from a young age as we navigate Polly’s home and school life.

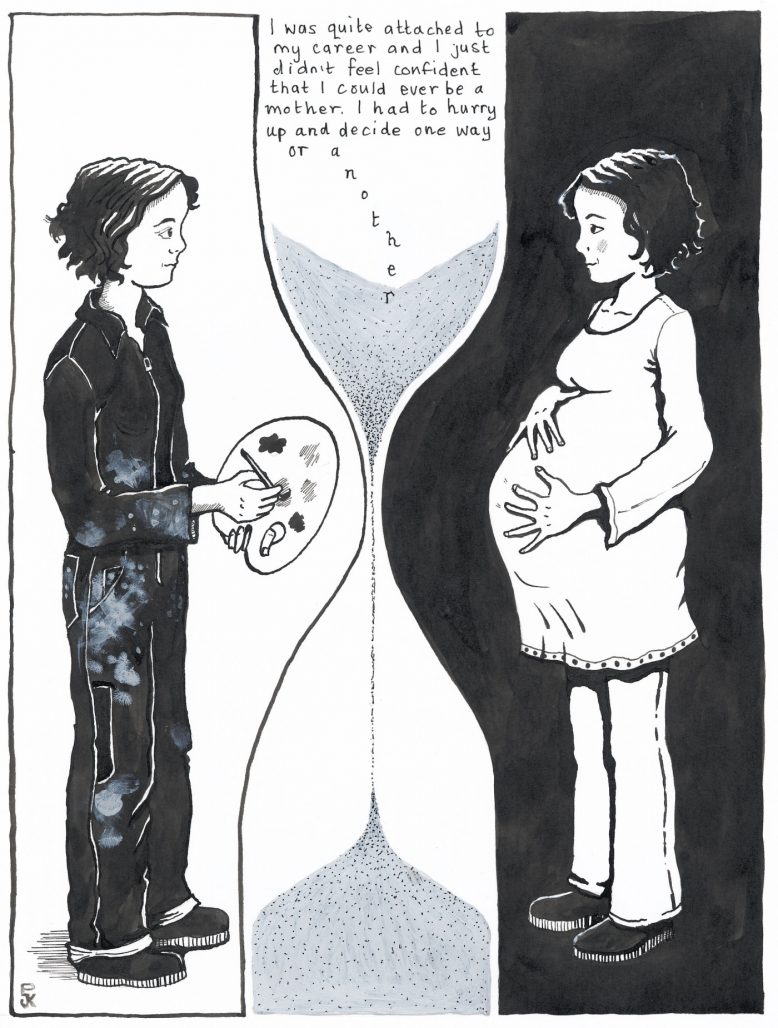

We follow the pair of friends as they graduate school, go off to college, experiment with lovers, find partners and eventually try to conceive. Polly focuses on her life’s passions of art and drawing while dealing with chronic illness, which is later diagnosed. In one panel, April calls Polly on the phone to announce her pregnancy with her first child. Polly is elated for her friend and at the same time she wonders when and if she will find a partner with whom she may conceive with.

After a discussion about parenthood, Polly and her partner Jack decide to try and conceive. The frankness of how Polly and Jack talk about whether or not they wish to become parents was refreshingly honest. It demonstrates that the path to conception isn’t a binary between jubilation and horror.

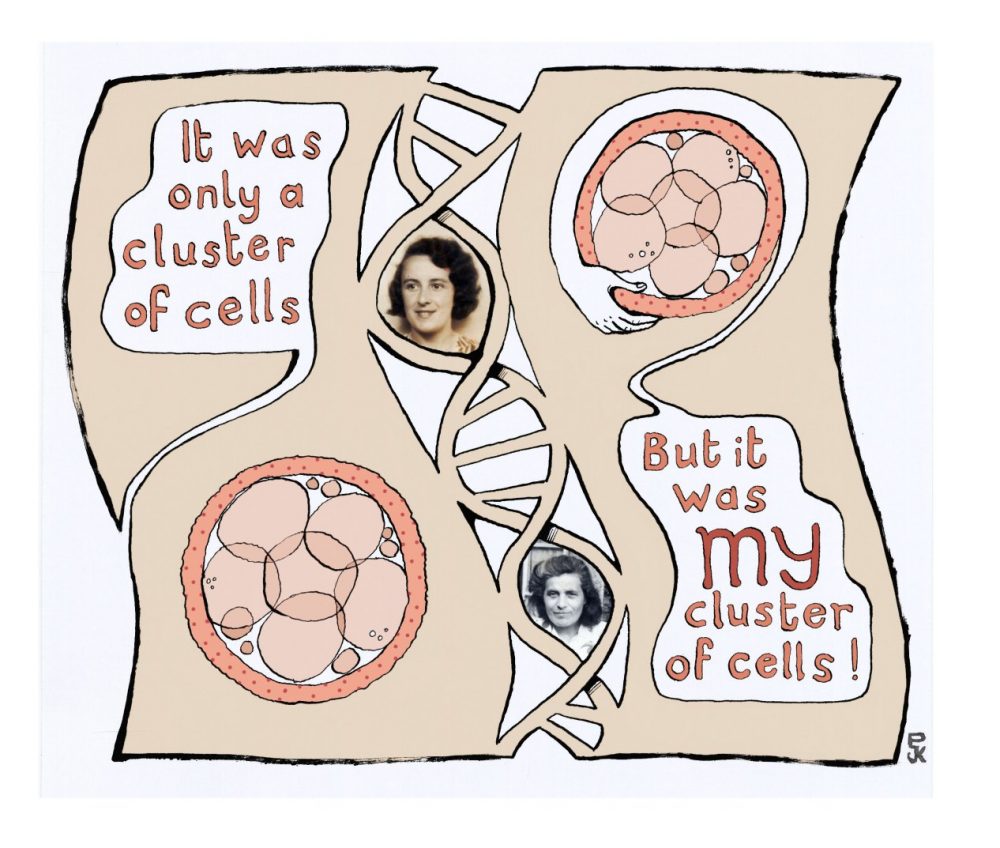

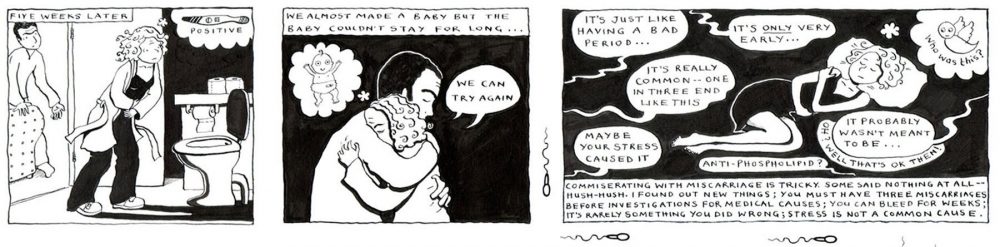

Through out the novel we experience Polly and her partners attempts to conceive, their success in doing so and numerous miscarriages. We watch as Polly struggles with how she sees herself and how others see her as friends go on to have more children. Polly and Jack’s emotional and physical pain around miscarriage are visceral. The joy of conception, the shock and feeling as if your body is betraying you and the search for why.

We discover along with Polly about her chronic illness and how she comes to reengage with who she is: an artist, an illustrator, and someone with intrinsic worth–casting off the auspices of societal expectations. The graphic memoir traces how society influences the way we think about being and conceiving and the pressures that come along with this. So, I asked Knight what she thought about societies perceptions and how we define what it means to be ‘enough’ (enough for ourselves and for society)?:

Knight: “Unfortunately, we live in an excessive consumer society where it serves capitalism to have more, better and new everything – and we are slaves to advertising and presentations of what a good life resembles. This can result in feelings of marginalisation and inadequacy if yours doesn’t resemble it. Especially at this time of year – cosy ‘family’ adverts (including children) posit what is the norm, when it isn’t the norm for everyone and there’s no reason why the images they present should be interpreted as such.

“I think women are judged more readily over their reproductive choices in ways that men are not. Our worth and value to society is so tied up with our relationship to children, when, ideally, we should be valued as autonomous human beings. So, if your choices are authentic, and deep down you know they are right for you, then they are ‘enough’ and ought to be respected as such. Before all women can feel like they are enough, society needs to accept that biology isn’t necessarily destiny. Anyone who menstruates ‘uses’ their uterus ‘enough’ – it doesn’t have to be used to grow a baby.”

Knight was quick to remind me that being ‘enough’ wasn’t just an issue women deal with but one every human must contend with. Knight’s understanding and empathy of how miscarriage impacts the partner as well as the self and her eloquence of expression belie the kind of person she is–someone who thinks and feels deeply about how their words impact others and this is especially true for how we speak about pregnancy.

Ayres: “Why do we have such a hard time talking about miscarriage?”

Knight: “It’s such an emotive subject immersed in grief for many people. I suspect that people avoid talking about it because they are afraid of saying the wrong thing or triggering outpourings of sorrow. Or people don’t know how to handle strong emotions and would rather not risk it. However, I think that stigma has a lot to do with it. Historically, menstruation has been derided, conflated with dirtiness or been the subject of delusional religious and mythical beliefs, and, along with menopause, is often the subject of off-colour jokes. Many cultures, including my own, cast blame on women for miscarriage, too, so this exacerbates the stigma and taboo.

Knight: “In some parts of the world women have been jailed and criminalised for having a miscarriage! It has erroneously become caught up with pro-life – yet another way to threaten women’s bodily autonomy and thus their readiness to be open about problems when they most need help. Of course, it involves women’s body parts that are private, and death, to which we are also averse to talking about. Also, in the public domain, women’s bodies are often sexually objectified for the purposes of selling products – that’s part of how our society values and commodifies women – so talking about miscarriage might shatter this illusion and pose a threat to the status quo. I think it’s also part of pronatal ideology – don’t talk about pregnancy problems or they won’t want to sprout! Having said all that, it is a private issue that many people choose not to talk about – and that is to be respected as much as women’s rights to talk about it if they wish. What we really don’t want to do is to shroud it in silence, because this causes isolation and loneliness.”

Identity & Having it All

I read Knight’s graphic memoir in one sitting. I was struck by how much I identified with her struggle to embrace and express her identity. To manage societies expectations for what occurs (or doesn’t) in my uterus. I forgot what honesty about these struggles looked like or the freedom that comes from simply admitting that you don’t have all the answers or that you are scared. I’ve become accustomed to the narrative framing that comes along with posting on social media, the one that says not only is it possible to have it all, but it’s easy too.

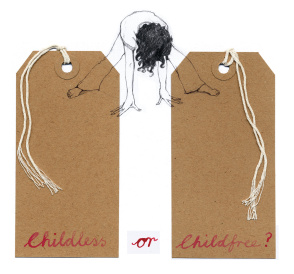

Ayres: “One of my favorite parts of the book were the ‘child free, child less’ panels, with the final one being “I’m just me.” Can you talk more about your journey to reclaim your identity, I feel like it’s such an important part of your book. That we aren’t (or at least shouldn’t be) defined by whether we do or do not have children…”

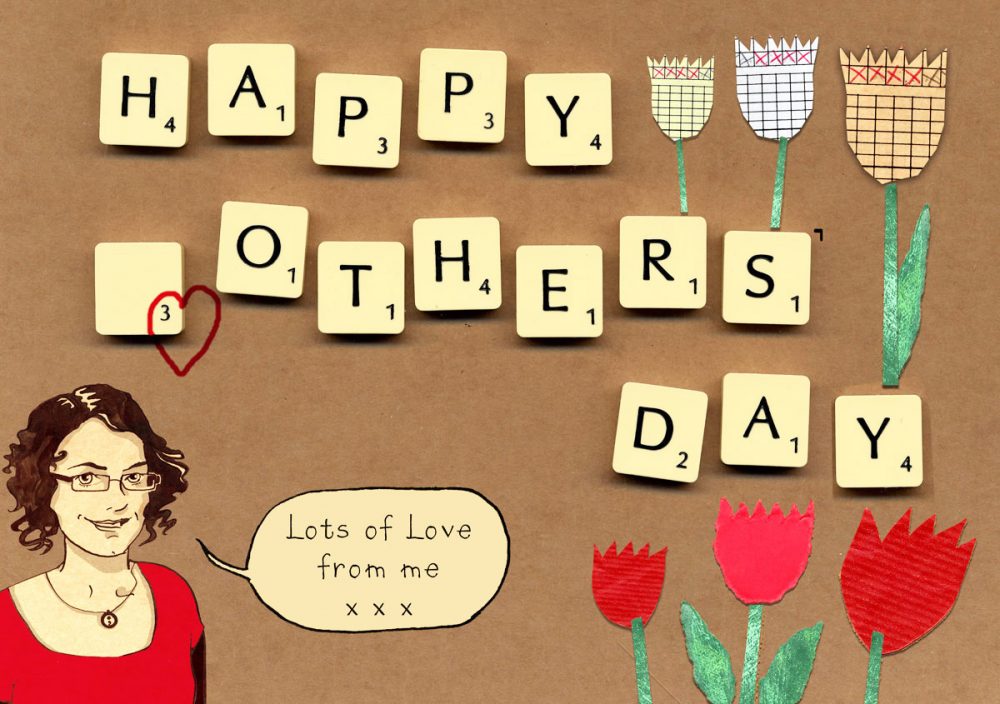

Knight: “In the book I say that I already had an identity I was happy with (as an artist and writer), but it is society that defines women as lacking something (childless) when they don’t have children. You only have to read celebrity magazines and their hounding of Jennifer Anniston’s uterus for a prime example. Why don’t they obsess over her skills as an actor, instead? It comes back to women’s value to society, and the media is a feedback loop for this. Of course, I grieved about not being able to have a child, but the way our society defines and judges women who don’t have kids is marginalising and unhelpful. Why label a person by what they don’t have? I have legs but never became an ice-skater (though I might have enjoyed that), but society isn’t obsessed over how I use my legs; it’s obsessed with my reproductive status.”

Knight: “Using my talents and creating work about this issue went quite a long way to re-establishing my identity. I made ‘Childless? Childfree? Neither, just me!’ as a response to society’s labelling of women without children rather than accepting them as autonomous human beings. I found a renewed sense of purpose and enthusiasm in my creative life, which was inextricable from my sense of self. Putting the work online on my social media platforms also helped because I was saying this is me; this is what I do and who I am. I purposefully placed my comics in the same space as other people’s family and children photos, on Facebook, because creativity isn’t only my job – it’s a huge part of what I live for and what is important to me – just as important as kittens and kids are to others! Always having had this vocation and drive helped greatly in not being able to have children, because I already had a solid underpinning of identity. I also joined online groups, such as Gateway Women, for people who are ‘childless-by-circumstance’: Connecting with so many others in a similar position helped me to feel less like the odd one out.”

Ayres: “What has the reception been to your book and comics; anything that has particularly surprised you?”

Knight: “Due to their personal nature, I was tentative about posting the shorter comics on my social media platforms/ blog at first, but overall the response was very connecting and led to conversations with friends that I might not otherwise have had. Some women wrote to me to thank me for expressing things on their behalf that they felt unable to. Many of those comics have now been licensed for use in various books and academic journals, which is something I didn’t expect when I made them.

“I’m also really pleased with the response to The Facts of Life so far – I’ve received similar emails from people thanking me for writing the book and that they found it very relatable, especially the 1970s childhood parts. I’m pleased that men are also enjoying it (some great reviews have been by men): There is an incorrect assumption that this is a subject matter for women, but miscarriage affects men as well as women, as does the decision over whether or not to have children. I was also overjoyed to discover that my book was on sale in City Lights bookshop – for my book to be residing in such a significant venue in literary history felt rather gratifying. I was glad it hadn’t been published in hardback!”

Forward

When I read through Knight’s responses to my questions I immediately realized how much I framed the experience of fertility, conception and the concept of becoming a parent using conventional narratives. Knight continued to remind me how we are and should be moving beyond a discussion of paternity being a binary choice between child and career.

Knight: “Feminism has been having this conversation for decades, and it’s thanks to that for improvements in family policy and paternity leave (especially if you live in Iceland or Sweden – the rest of the world has a lot of catching up to do!) In those countries women’s work is valued and it’s easier for women to work and bring up a family– we’re back to women’s value and place in society again! Thankfully, the conversation continues to grow, especially as today’s economic circumstances mean that it’s increasingly the case that both partners must work several jobs just to make ends meet (it’s always been the case in poorer/working class families).

“I suppose this will eventually override the old-fashioned notion that a woman might be selfish for wanting to expand her horizons and economic autonomy by, horror-of horrors, working! I think conversations around choosing not to have children, or to limit family size, will become more acceptable as human impact on the environment worsens and the consequences affect wider areas of the world. I wonder if this will become the rub of the conversation rather than it being about the choice between children or career.”

As someone who is trying to understand and navigate what value they provide to the world and trying to parse through their own shifting perceptions on identity, I find Knight’s work to be especially freeing. The Facts of Life shows us life is not always clean, it’s not always pretty or easy but we all share in these moments. These moments of hardship, of questioning, of joy, loss and discovery and that is simply, a fact of life.

This is part one of an interview series conducted about fertility and the choice to become a parent. The first part of this series has been with illustrator and writer Paula Knight. Her graphic memoir The Facts of Life was published in 2017 by Penn State University Press. You can find more of her work on her website. The second part of this interview series with Marnie Galloway will appear on Wednesday, December 20, 2017.

Comments are closed.