Jeff Lemire is one of the most prolific comics creators currently working in the industry. Following his breakout graphic novel Essex County, Lemire has explored themes of childhood and innocence lost through contemplative and grounded graphic novels like Underwater Welder and through genre series like Sweet Tooth and the breakout hit Descender, which was recently optioned for a film adaptation.

I recently sat down with Jeff Lemire to discuss his storied career. We explored his early career, the difference in perspective that fatherhood has provided him as a writer, and the horrors he learned were perpetrated by the Canadian government against the First Nation aboriginal community as he prepared to pen Roughneck. The word “X-Men” was also mentioned.

Alex Lu: How’s Descender going?

Jeff Lemire: It’s going great. Dustin’s finished issue five and he’s working on number six. I’ve written eleven scripts, and the reception has been as we possibly could have hoped, both critically and in sales numbers.

Lu: Eleven scripts? You’re pretty far ahead. Is that how you typically work?

Lemire: Yeah, I work really far ahead on everything. I’m juggling so many projects right now that the only way I can handle it is to be so far ahead on everything that I can take a couple months off one thing to work on something else. Right now is my time off from Descender so I can let it sit and come back to the scripts once Dustin draws them.

Lu: Because you work so far ahead, do you often find yourself revising older scripts based upon where the later ones take you?

Lemire: Oh, absolutely. That’s a real benefit that you don’t often get working in monthly serialized comics. When you’re doing the monthly schedule, most people are getting the scripts in right on time and flying by the seat of their pants. It’s nice, especially on creator owned stuff, when you have the opportunity to let the story take you wherever it wants to go and if you go in a direction you hadn’t anticipated, you can go back and rework earlier things to make everything line up. It’s a unique adventure.

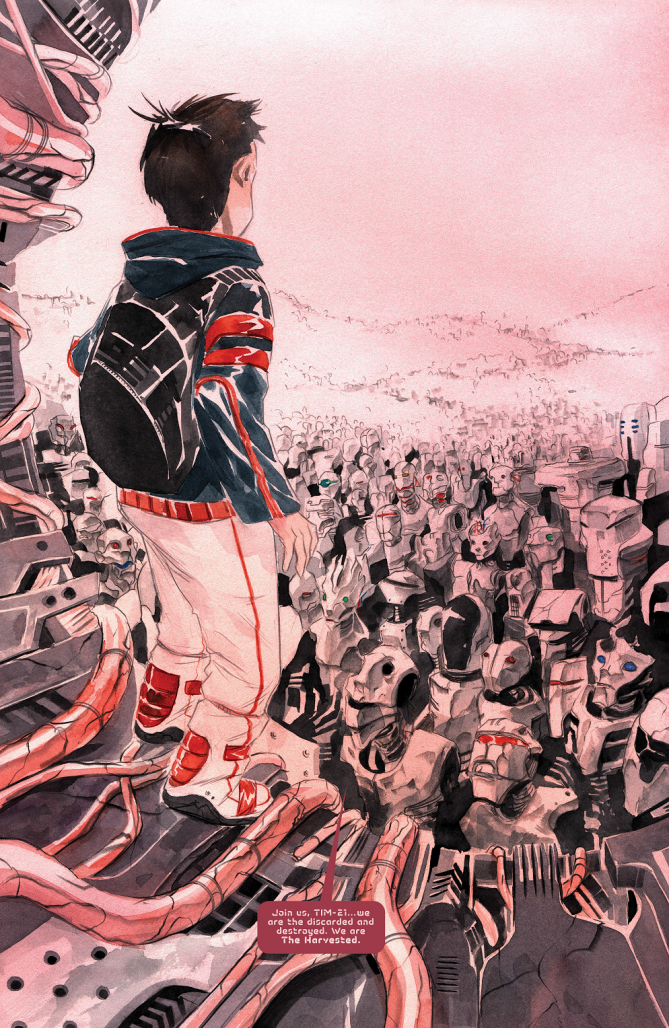

Lu: In the third issue of the story, you introduce the concept of a robotic afterlife. Is this something that was in the story from the onset or was it something you came up with later?

Lemire: It wasn’t in the initial pitches, but it emerged early on in conversations with Dustin. I don’t want to give away too much about where the story is going, but the sequence you’re talking about came out of an idea Dustin had after reading the initial pitch.

Lu: What was the initial pitch like and how far have you deviated from it?

Lemire: It’s pretty close to the initial pitch. The story should run for 23 to 40 issues, and I think we’ve added one major character who’s now pretty integral to the whole thing, but other than that…I spent a long time on the pitch before showing it to Dustin so I had the building blocks in place. It was a matter of fleshing the characters out and letting some of them breathe and develop. Sometimes, seeing Dustin’s art will give me ideas for new directions or I’ll fall in love with a background character and I’ll start writing a bigger role for them because I like the look of them and want to tell a story about them.

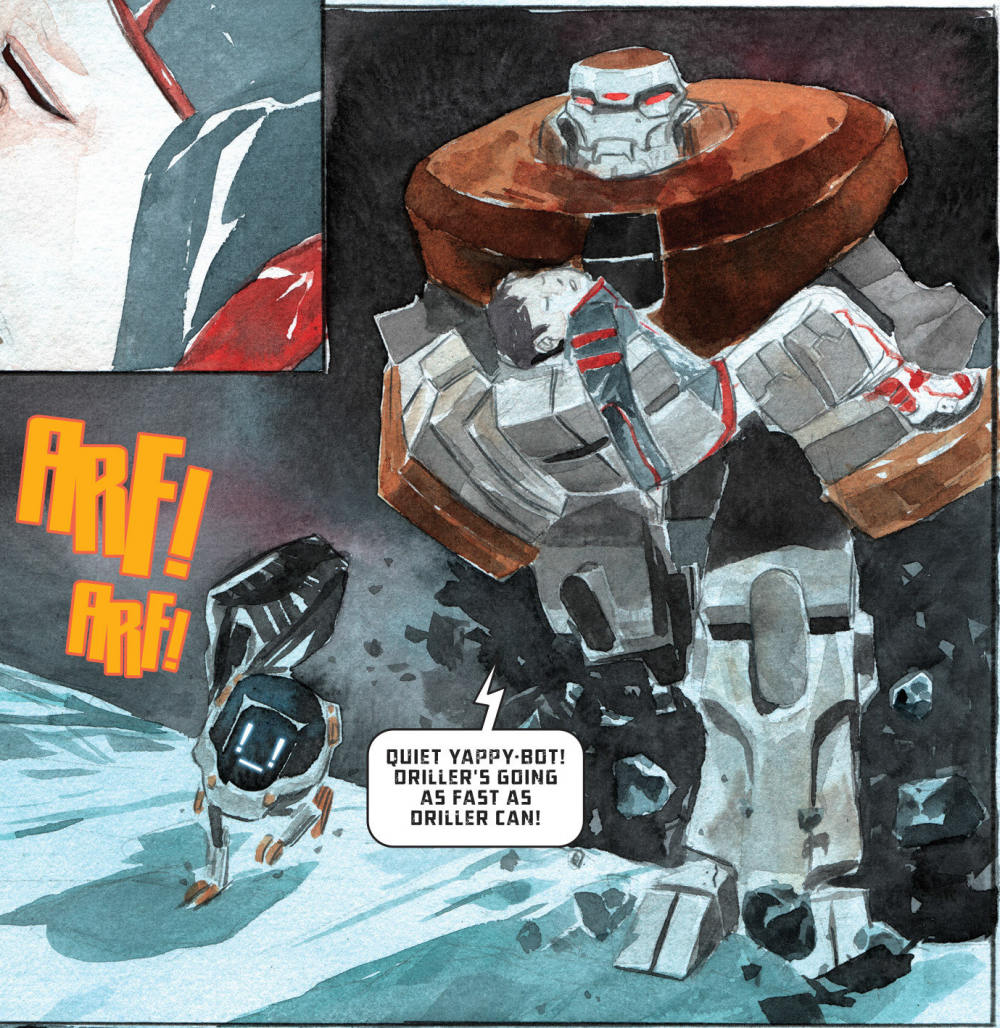

Lu: I think one of the breakout stars of the first arc is the Driller bot. I didn’t think he’d make it past his introductory issue, but he’s still around!

Lemire: Driller was always one of the main characters. He, Tim, and Bandit were always going to be a threesome, right from my initial pitch. I was surprised to hear that people didn’t think he was going to he was going to stick around, but he’s here to stay. I always like my big dumb guy and he gives a good balance to the rest of the group. Physically, the difference between him and Bandit is a great juxtaposition.

Lu: The relationship between Tim and Driller seems similar to the one between Rocket Raccoon and Groot.

Lemire: Yeah, I guess! Driller has some secrets that Groot probably doesn’t have, though. There’s a bit more to Driller than what people are getting right now. We’ll leave it at that.

Lu: What’s been the most exciting part about working on the series so far?

Lemire: Oh, it’s definitely been seeing Dustin’s art. It’s the first creator owned book I’ve done that I haven’t drawn myself and it’s a real thrill to invest so much into something and then share it with someone. Then you’re surprised by how that someone brings themselves to it as well. Seeing these ideas that I came up with being realized and built upon by Dustin is a real thrill.

Lu: Were you thinking of Dustin when you came up with the pitch for Descender?

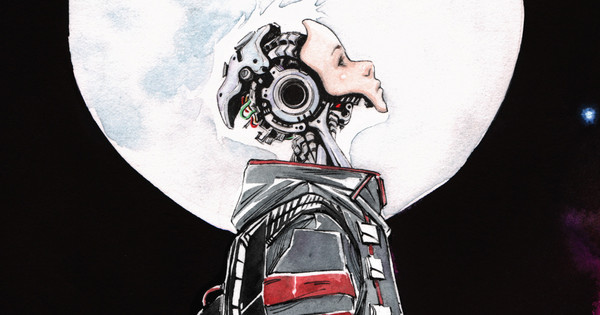

Lemire: He was the first artist I asked. I don’t remember if I had him in mind when I was writing the initial pitch, and I don’t think I did. However, now I can’t imagine the series without him because his watercolor style has become so indicative of what people think of when they think of Descender.

Lu: Dustin’s art is a great yet unexpected choice because of the way his natural watercolors stand in contrast with the cold and mechanical feel of this futuristic world.

Lemire: I think the art style he’s using embodies the whole core of the book. It’s a science fiction book about machines and things that are technical, but it’s executed in a very organic way. That mixture of the human and the machine embodies Tim and really, the heart of the book. It ends up being perfect in that way.

I think Tim is the most human character in the book, which is ironic given that he’s a robot. I think robots are the ultimate symbol of human arrogance. It’s us playing god, creating something in our own image. We’re seeing this world that’s outgrown us. These machines grew beyond us and we couldn’t handle it so we destroyed our own creations. I think that says something about us.

Lu: What were you influenced by as you developed Descender?

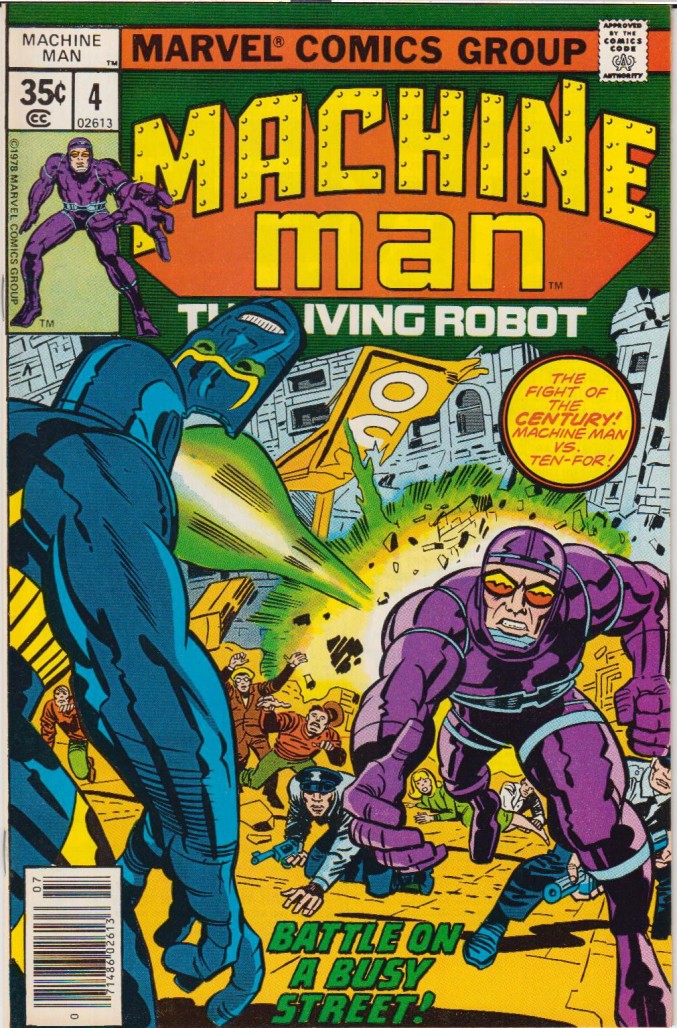

Lemire: It’s always a tough question to answer because I never remember exactly what I was into when I develop a concept. It’s a weird alchemy how any idea comes together. I can’t think of a lot of real sci-fi I was into at the time. One thing that influenced me a little bit was Jack Kirby’s Machine Man. I was really into reading all the 70s cosmic stuff he was doing at Marvel. I don’t think you see a lot of it in Descender, but I think it’s there somewhere. You know, I don’t know, I feel like I’m avoiding the question but I really don’t remember what I was into it. Sometimes these things happen real fast and these things just spill out.

Lu: How long have you been working on Descender?

Lemire: I think I started working on the pitch last February or March. I knew my DC exclusive would be done in June at that point so I was starting to develop things I could work on with Image or elsewhere. That was around the point Dustin got involved, but I had been working on concepts six to seven months before that as well.

Lu: Did you find it challenging to work with Dustin given that his style is so different from your own?

Lemire: Not at all. I think if you want someone to draw just like you, then there’s no point in collaborating at all. You try to find artists whose work you like and respect and you work with them because you want them to be themselves. It’s very easy for me to be completely hands off when I’m not drawing something and give my artist, in this case Dustin, the room to let him be himself. I respond to his work emotionally and aesthetically so I wouldn’t want him to be anything other than Dustin. I think it’s a very easy collaboration. There’s a lot of mutual respect and trust.

Lu: A lot of your creator owned work has been published in the form of a graphic novel. What made you decide to produce Descender as a monthly?

Lemire: The biggest creator owned book I ever did was Sweet Tooth, and I did that for four years so doing another was nothing new for me. I think I’ve really grown accustomed to a monthly format and I even kind of prefer it. In a film, you have two hours to tell a story and develop a character, whereas in television you can spend multiple seasons and many hours developing characters and plotlines. Comparing graphic novels to monthlies is similar because in monthlies you have more time to develop everything and execute stories. You’re not trying to boil everything down into an easily digestible three act structure like you are in a graphic novel.

I prefer that longer format monthlies provide; the ability to take an issue and focus on one character per month. You don’t have to be so focused on the amount of space you have to play with or the space you’re wasting in order to tell a story. I just finished a graphic novel, but I think I want the next thing I draw to be a monthly. I ultimately prefer things that way.

Lu: With monthlies, do you ever worry that you might wander so much that you lose sight of what you originally wanted to say with the work?

Lemire: No, because what I start with is usually very simple. One or two sentences. A simple core idea. It’s never anything too complicated or too complex. You’re not starting with a byzantine plot you’re trying to hold onto. It’s easy to remember a core idea, so it’s never been something I’ve been worried about. Plus, the more you get into a book and develop the characters, the more you feel like you know them and the easier it is to find your way through a work.

Lu: How long does it take you to find that kind of rhythm with your characters?

Lemire: It varies from project to project. Generally, with stuff like Descender, it develops pretty quickly. Once you write the first issue, if you’ve done it well, you get a pretty good sense of who these characters are. Especially when you’re the creator of these characters, you already know these characters better than anyone else so it’s not hard to find that rhythm as long as you stay true to and build off of your original idea.

Lu: Your story in the Vertigo CMYK Anthology, “Sweet Tooth: Black,” really struck me because it caused me to develop an empathetic relationship with a group of characters in a very short period of time.

Lemire: Thanks. I actually think it was a mistake to do that story. I was happy with how it came out but I had already told the Sweet Tooth story and I was really happy with the ending. After I made the Black story, I wondered why I went back to something I was happy with. I’m glad it affected other people.

However, doing more short stories is something I would love to find time to do. These days, though, I seem to jump from one project to the other and don’t have as much time to experiment as I used to. With this story, I think I just missed the character a little bit and thought an eight page zero issue would be a good way to scratch that itch without committing to something bigger, but in hindsight, I probably wouldn’t have done it. I don’t think I’ll ever go back to any of my stuff again. When something’s done, I usually move pretty quickly.

Lu: Something like Essex County seems like it still has room for development.

Lemire: Yeah, but I would never go back to it, either. I’ve had people ask me, and I feel like I’m a completely different person than I was when I wrote that book. Each book marks the place you were in when you did it, and it’s really hard to go back and be the same person you were. You mentioned holding onto that core idea and not losing it, but when you finish something it goes away and you get another core idea.

It’s really hard to go back and find that original idea, especially when that idea inspired your first book. I was in a very different place compared to where I am now, so it’d be very difficult to do more Essex County that would fit with what I was doing before. Plus, Essex County is almost ten years old and people are still enjoying it and it still sells very well so it still has a life and I don’t want to mess with that. I want to do new things.

Lu: Would you want to go back and explore the more realistic space you explored with Essex County, though?

Lemire: Absolutely. That’s the Simon and Schuster graphic novel I just finished. It’s not another chapter of Essex County, but it’s a return to the grounded family drama work I was doing from a different perspective. I love doing genre books like Trillium and Descender and I think I always will, but it’s also important for me to balance that work with stuff like Essex County to make sure I don’t stray too far away from reality.

Lu: And this new book is called Roughneck, right? What did you discover the difference in your headspace to be between this book and Essex County?

Lemire: Yeah…I’m a totally different person. When I was writing Essex County, I had never published anything and nobody knew who I was so there was no expectations on the work. I was still finding myself as a creator and on a personal level, I wasn’t a parent yet. I am now, and that dramatically changes your life and everything about your perspective on life. I’ve had a certain amount of success now so I get to do comics every day and make a living off it whereas I was struggling to write Essex County while working day jobs.

Lu: Even though you weren’t a father while you were writing Essex County, there are recurring storylines in that book and your other works about what it means to be a kid and to grow older and lose your sense of innocence. What is it about childhood that you find so fascinating?

Lemire: I have no idea! It’s one of those themes that I keep coming back to and keep exploring. To sit back and analyze why I do that is not really how my mind works. I do the analysis through my comics, so I don’t know what it is about childhood, innocence lost, and fatherhood that makes me keep coming back to them, and sometimes you don’t even want to analyze, think about, or articulate those things because you don’t want that well your ideas seem to come from to go away.

On a basic creative level, I have always enjoyed writing from a child’s perspective. It comes very naturally and I seem to have a knack for it. I think I’m interested to look back in a few years and compare the stuff I wrote before I was a father to the stuff I wrote after and see if the early works were about being a child while the later ones are about being a parent.

Lu: How has having a son influenced your depiction of kids?

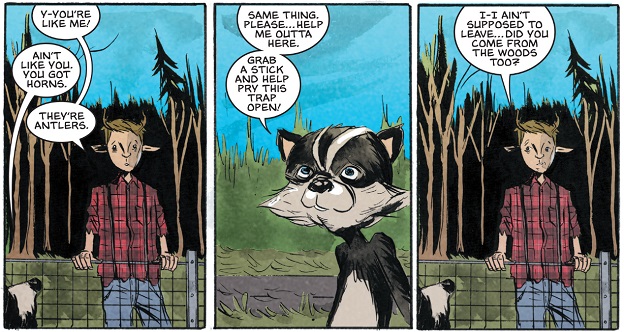

Lemire: I think I have a much better sense of innocence and the sense of wonder through which they see the world. I think that’s why Sweet Tooth is the way that it is. It’s about this completely innocent kid slowly discovering the world around him, and I think Descender is much the same.

Lu: Do you think it would be accurate to say that before you had your son, your stories about childhood were influenced by your childhood?

Lemire: Yeah, I think that’s accurate. I think Essex County was about me fictionalizing and dramatizing my childhood. It’s where I grew up. On the other hand, Sweet Tooth and Descender are much more about my fears for my son and me wanting to protect him and his perspective about the world.

Lu: Now, tell us a little more about Roughneck.

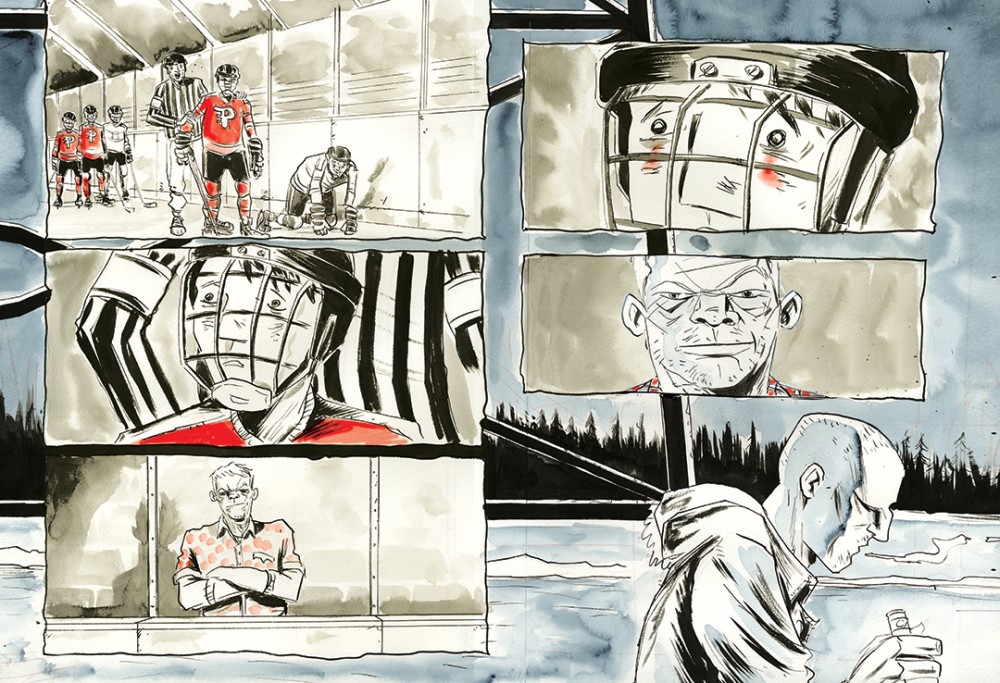

Lemire: It’s a 275 page graphic novel written and drawn for Simon and Schuster for a Spring 2016 release date. The story focuses on a guy named Derek who is an ex-NHL tough guy whose career ended in disgrace after a violent incident. Since then, he’s returned to the remote First Nation community where he grew up in northern Canada. He’s been stuck in this small town and a bad place, drinking too much and fighting too much; not really moving on or finding a new path for his life after hockey left him behind. Then, his sister, who ran away from town when she was 15, comes back into his life. Her return triggers the creation of a new path for both of them. It’s a story of brothers and sisters, healing, and them reconnecting with the land and their Cree heritage. They find a healing in the old ways of their people.

Lu: Did you do a lot of research for this project?

Lemire: Yeah. I never feel like I’ve done enough because I’m not aboriginal and don’t have any native blood. So, as a white guy writing about aboriginal people you always feel like a bit of a pretender, but I did as much research as I possibly could. I spent a lot of time in one of the First Nations here in Ontario, just meeting people and talking, trying to understand the community more and being inspired by it.

Lu: What was it that made you want to tell this story?

Lemire: A couple of things. I got really inspired by this Canadian novelist, Joseph Boyden. He’s done three novels now, and they’re all favorite books of mine. He writes about a lot of the northern communities in Ontario and I just fell in love with that community through his stories and wanted to learn more about them. That created a big gap in my understanding of Canada.

Canada is a very big and diverse country, but there wasn’t a large native community where I grew up. I had no firsthand experiences with aboriginal people and their culture. I realized how ignorant I and so many other Canadians to the first peoples of Canada, so the project became a way for me to learn more about that culture and hopefully help others connect to that culture as well.

Lu: In American schools, we’re taught quite a bit about the current and historical treatment of Native Americans. How were and are the aboriginal people of Canada treated?

Lemire: Horribly. We basically committed cultural genocide and we don’t even learn about it in school. You see a headline every once in a while, but we really have no understanding of what really happened to these people and how these communities found themselves where they are today, which is marginalized and isolating. It’s a third nation living in a first nation, and when I started to learn about that it triggered my need to explore and learn about the positive aspects of First Nation culture.

We so often see the negative stories that focus on the hardships the people face and the end result of years of abuse that we’ve inflicted upon them. You never see the beautiful and amazing parts of their beliefs and their culture. They’re a vibrant and resilient people, and these are the things I wanted to communicate to other white Canadians through my work.

Lu: You never learned about the suffering inflicted on aboriginal people in school?

Lemire: Not really, or at least not nearly as much as I should have been, that’s for sure. Also, I’ll be fully honest, it’s hard for me to go back in my mind and remember what I was actually taught in school and how much I was paying attention. Nonetheless, I’m not being hyperbolic when I say there was a cultural genocide. The church and the government of Canada basically wiped out native culture and took their children, putting them in residential schools where they were forced not to speak their language. They never saw their parents again, and in many cases they were sexually and psychologically abused by the people running these schools. This went on for decades until the 80s and 90s, and most Canadians aren’t aware of exactly what we did to them. I think it’s something we need to be educated about more because it’s a huge part of our culture and country.

As much as I love Canada…you know, to go back to the subject of my early work versus now, Essex County was my perspective on Canada as a naive 20-whatever year old who loved the classic old-age feel of hockey and nostalgic things that we positively associate with Canada. Roughneck is the 39 year old me who’s now looking at Canada and realizing the country and history is a lot more complicated and shameful than I realized back then. There’s a pretty stark contrast between my perspectives, and even though I use hockey as a central metaphor both, I use it for two very different reasons.

Lu: It’s incredible to me that these shameful practices persisted into the 90s.

Lemire: Yeah, I think the last schools closed in the 90s. I can’t speak to the history of abuses and when those stopped, but it’s clearly not something that’s way back in our history that we can just forget about. It’s still very recent and very much being dealt with by modern aboriginal communities.

Lu: Race issues are a huge topic in America nowadays. Is it often discussed in Canada as well?

Lemire: Yeah, you know what, as much as I’ve bashed Canada in the last bit of this interview, I think that’s one spot where we’re a lot further ahead than you guys. It’s easy for me to say sitting in Canada, not being a part of your country, but I do think we’re a bit more progressive in terms of race relations.

I happen to live in Toronto, one of the most multicultural cities in North America, so maybe my perspective is a little different because so many different cultures and races live together here. It’s so different from what a lot of the US is experiences. In terms of First Nations and aboriginals, though, we’re shamefully ignoring another huge problem.

Lu: I consider myself blessed to have grown up in a community that was relatively racially diverse. Was your childhood community the same way?

Lemire: No, not at all. I grew up in Essex County, which was a tiny farming community in southwestern Ontario, was 99.9999% white. There was a lot of ignorance and there still is in these small towns about different cultures and races. You can’t help but be surrounded by that, growing up there, but I was lucky because both of my parents were very progressive and open minded and accepting of other races when I was young. That influenced how I grew up. I moved to Toronto when I was fairly young, so I came of age in an extremely multicultural city. That, combined with the basis my parents gave me led to me becoming a very liberal-minded person.

Lu: Was there a transitional shock going from a very homogenous community to a very diverse one?

Lemire: No, I don’t even remember thinking about it. I think it was all part of the excitement of being in a big city and being surrounded by all these new people and all these people that wanted to create art. Being young, it was all just newness and excitement, rather than anything I needed to adjust to.

Lu: It’s interesting that, even though you came of age in a metropolitan area, many of your stories take place in the countryside. What is it about the province that keeps calling you back?

In the case of Essex County, it was a story about where I grew up and how I grew up. Sweet Tooth was set in a rural post-apocalyptic setting because I was so sick of seeing post-apocalyptic cities in every movie. That book was also a return to nature through human-animal hybrids and it just felt more appropriate to set things in more bucolic settings. Roughneck is also about a very specific small town that’s very different from Essex County, being set in one of our First Nations.

Lemire: I’m not sure. It’s my first time working with a non-traditionally comic publisher. Simon and Schuster, being a book publisher by trade, has a different way of operating and promoting the book. I’m not really sure what their schedule is in term of releasing previews, but I do know they work a lot further ahead than comics publishers which is why the book won’t come out until next year. So it’ll probably be a while.

Lu: What brought you to Simon and Schuster as opposed to Vertigo, Image, or Top Shelf?

Lemire: I think it was just something I hadn’t tried yet. I’ve worked with basically every kind of comics publisher from mainstream DC/Marvel to Top Shelf and the smallest indie publishers. I wanted to see what would happen if I did a book that was aimed at the traditional book market and built on some of the groundwork I laid with Essex County. I had a big breakout here in the Canadian literary market with Essex County and I feel like I never followed up on it. Simon and Schuster has a strong Canadian branch, and given the specific subject nature of Roughneck, I knew I’d need a publisher that understood what I was writing about and could get the message out in an accurate and big way.

Lu: I’m really looking forward to seeing how the book turns out. One final question: X-Men?

Lemire: I can’t comment. All I can say is that I am working on other stuff for Marvel, as Axel Alonso has mentioned before. The identity of those books will probably start to be revealed at San Diego Comic Con, but I’ll also say that you shouldn’t believe everything you hear on internet rumor sites.

Descender #5 releases on July 8th. Roughneck comes out in Spring 2016.

Wonderful interview.

great stuff. Good questions, great answers. He seems to have a really good plan with his work.

Comments are closed.