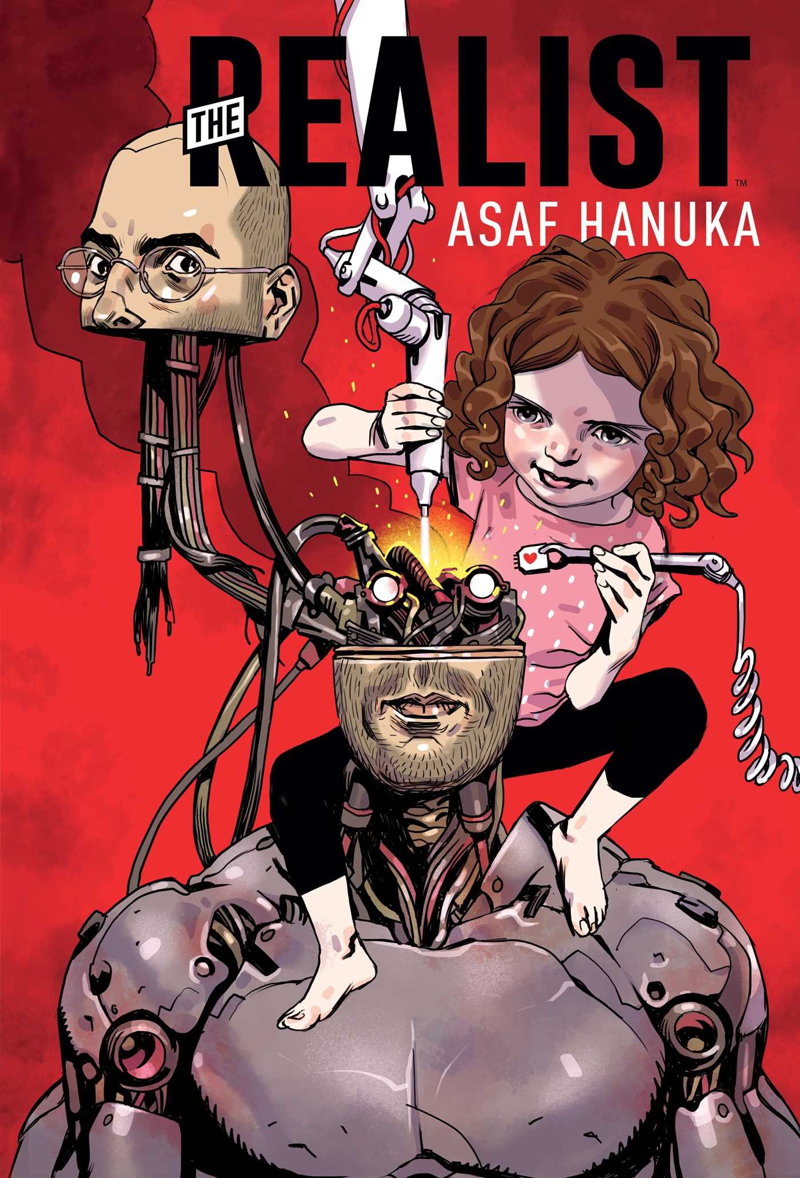

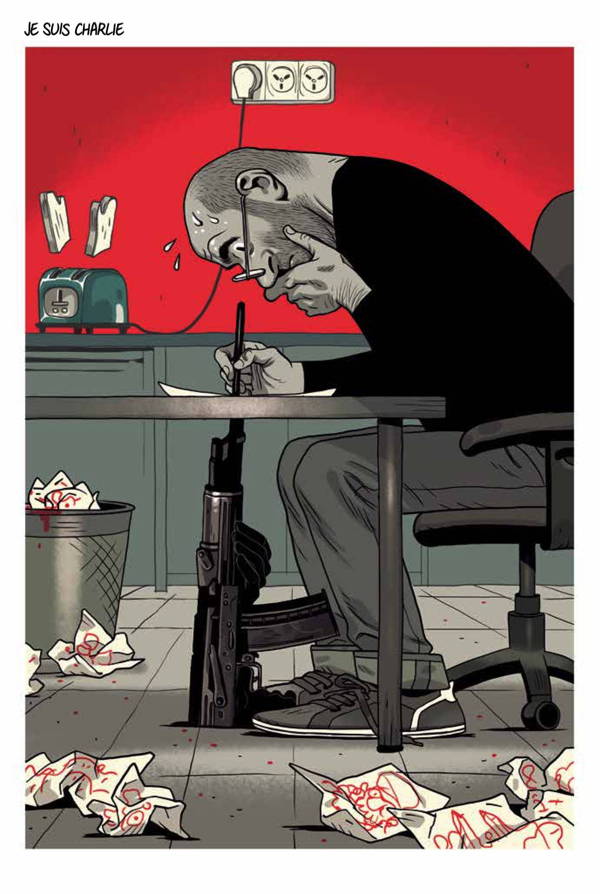

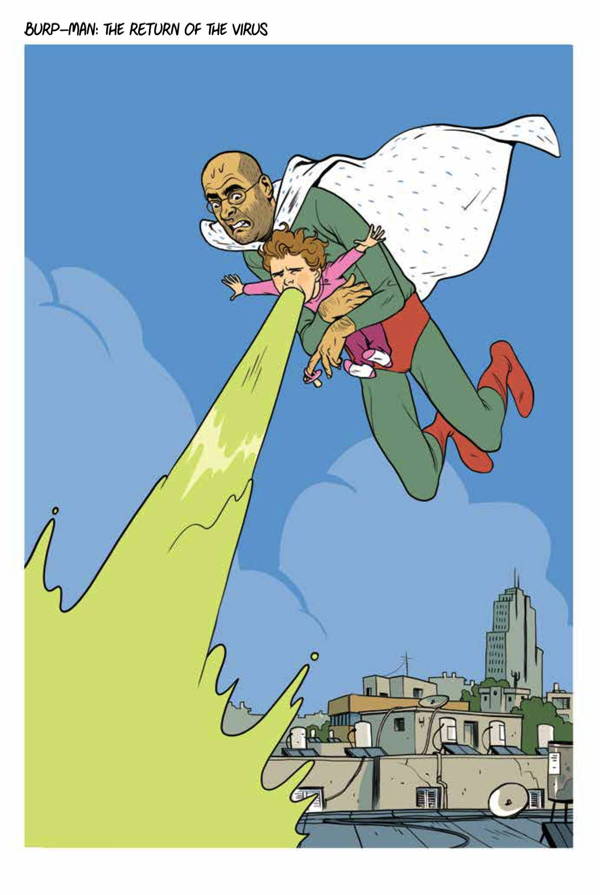

Asaf Hanuka’s webcomic The Realist has been running for years with a mix of withering self deprecation, family foibles and the occasional dark realities of life in Tel Aviv. As caustic as it can be, it’s also a humane and insightful look at how we process life internally and externally. It’s also funny as hell and beautifully drawn. The second collection of strips, The Realist: Plug and Play is just out from Archaia and it’s another quality outing.

Sometimes in collaboration with his twin brother, Tomer, Hanuka has been making fine comics for more than a decade. (They teamed up on their self published Bipolar and The Divine from First Second.) I was eager to dig a little into his working process and how the brothers developed their own unique styles. Thanks to Boom!’s Mel Caylo for facilitating this.

THE BEAT: Asaf, the last time we met was at the Jewish Museum up in Manhattan at a panel called “Who is the Parisian Roz Chast.” It was a tough audience of died in the wool free event attending seniors, and I was a little afraid….but everyone won them over. I have to say you were one of the stars though. And at the end of the night you were named the Parisian Roz Chast! Your comics are so dark and personal…what do you think is the quality in your work that won over the crowd?

HANUKA: It’s probably because I use weakness as source material. It’s very easy to feel empathy to someone who doesn’t try to sell you a better image of himself. My work is about accepting and admitting my weaknesses and making something creative out of it. Everyone has weaknesses and it’s comforting to see someone else presenting his collection without shame.

THE BEAT: What made you decide to make comics that are, to be frank, so firmly rooted in your own anxieties and worries?

HANUKA: The weekly deadline and the need to produce work fast. I don’t have much time to develop a story or think of complicated metaphors so I approach it like a reporter. I’m reporting on whatever happened that week in my head and in my life. Usually the good happy stuff is boring. Example: I went to eat pizza, it was tasty. There’s no story in hapiness. But if I went to eat pizza and it made me realize I will never be a ninja turtle, then it’s a start that could lead to a story. Anxieties are more fun and luckily I have plenty.

THE BEAT: there’s a recurring image of your head as a kind of tape player, or mechanism and the idea that somehow all of this is like a computer spitting out data. Your work seems so warm and in the moment though, I’m curious about what this metaphor stands for and where you got it?

HANUKA: That image was created after a few months during which I was constantly away from home, promoting The Realist around the world in variues comics conventions (The Realist was translated into 12 languages). I missed home but every time I called my wife the conversation was pretty much the same, like we were both on auto pilot. It was frustrating because words are so limited, for me. I can tell her “I miss you” but feel as if it’s the same broken tape playing somewhere in my head. In the image I tried to show that the most intimate feeling we have are communicated by cliches that kill any chance of intemacy.

THE BEAT: Do you ever worry about revealing too much?

HANUKA: I’m always worried before sending a new page to print. I fear it will be misunderstood or might make someone angry or just make people think I suck. but the worst times are when I don’t have any doubts. Usually it means the work is not really interesting and I didn’t take any risks. I think that good art includes a risk, in my case the risk is revealing because I do auto-biography. And sometimes I do reveal too much. I learned to live with it. It’s a dirty work but someone has to do it.

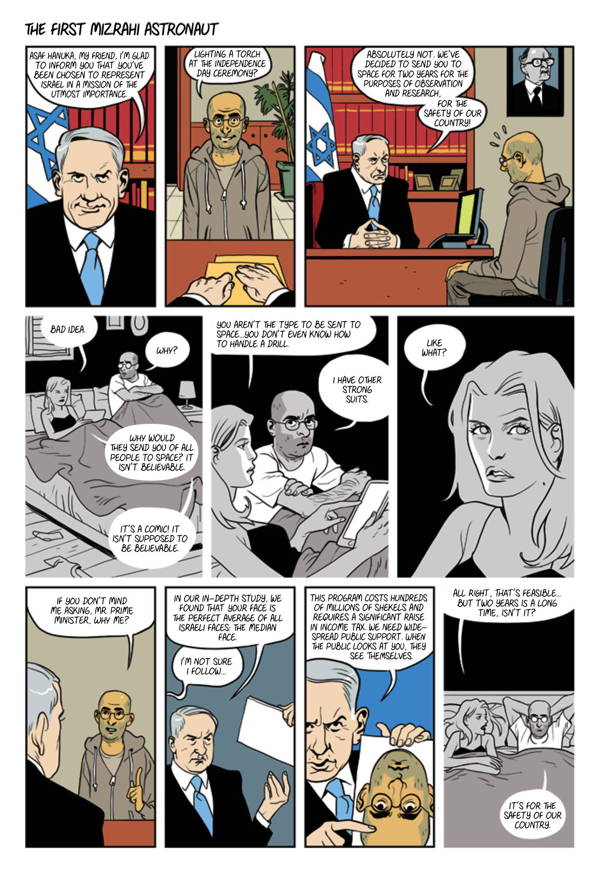

THE BEAT: Although you call your book The Realist sometimes it’s hard to see where what’s real ends and fantasy begins. In your comic about becoming an astronaut for instance, even though it it so patently ridiculous, you show a program of being tested and it has a very realistic FEELING. Is there anything in the book that actually happened or is it all magic realism?

HANUKA: It’s a paradox. I do whatever I can to be as accurate and realistic describing something which is completely subjective: a certain feeling or a thought. So I admit I’m not telling stuff exactly like it happened in real life. My wife never turned into a werewolf. But the goal is to be true and honest, and sometimes magical realism can make that work better than a realistic description.

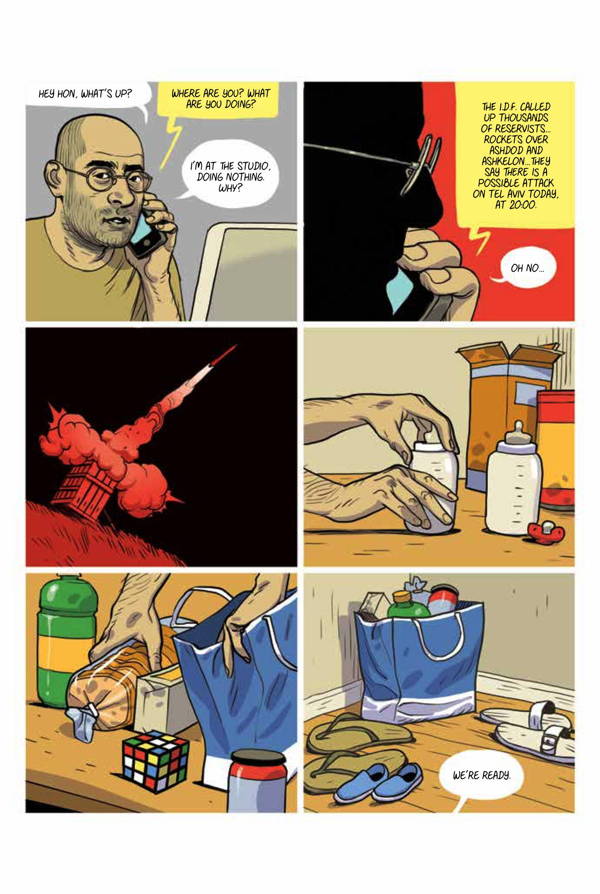

THE BEAT: Some of the scenes about life in Isreal are obviously real, including going to a bomb shelter when a rocket hits Tel Aviv. That was a real incident, but you frame it with a story about your family in a way that I thought was very powerful. Did you deliberately take an approach that wasn’t so direct about this very dramatic incident?

HANUKA: It’s true, that really happened, and more than once. It was pretty scary. A neighbour told us a bomb is going to fall on Tel Aviv at 8 in the evening, so we sat in the living room with the kids and waited for the siren so we know when to run to the shelter. We prepare in advance food and water in case it gets complicated. And then the siren starts and it’s total chaos, kids screaming, the building shakes and 10 minutes later we are back to our own apartment, back at the evening routine, brushing teeth and going to bed. I was amazed that we were able to go back to a routine so fast. As if nothing really happened. and when I followed the news on what was happening on the other side I realized that to compare to what happened in Gaza, we were really lucky. It was “nothing”. I tried to get that feeling across in the story.

THE BEAT: I’ve never really asked you about your twin brother, Tomer, also a cartoonist. You are identical twins and your art has a familial resemblance but very different in details. How did you two develop your own styles as artists?

HANUKA: Tomer and I grew up together in the same room, reading comics and drawing obsessively during most of our childhood. then, at the age of 21 Tomer moved to New York and I to Lyon, France. We spent the next 20 years in different continents. After a childhood in which we basically shared the same issue of X-men we were suddenly influenced by completely different sources and developing different approaches. While both of us are interested in telling stories I think Tomer has the ability to tell a whole story in a single image while I’m interested in using a sequence of images.

THE BEAT: I’m curious about how you two approached breaking in. Did you always plan to be a team or want to have separate careers?

HANUKA: Working together is a form of dialogue. We never planned it but during the years we have been far away we used it as a way to stay in touch: We started Bipolar (I worked with writer Etgar Keret and Tomer created his own stories) in which each of us did half of each issue. The last project we collaborated on was The Divine (with writer Boaz Lavie). It’s a different collaboration because we actually created the art together: I did the sketches and Tomer the ink and color. We recently worked in a similair way on a story for Attack on Titan called “Memory Maze” which Tomer wrote. It’s an amazing experience and I enjoy it a lot.

THE BEAT: How long will The Realist continue? Do you think you will ever run out of material?

HANUKA: I ran out of materials after the first 2 months but continued anyway for 7 years now, because I needed a job. I guess I will keep doing it until the newspaper cancels this page. I think some of my best work was produced when I wasn’t in the mood and didn’t have any ideas. Inspiration is the biggest enemy of creativity because it’s a fake promise that it’s going to be easy. It’s not.