I’m home for the holidays, and spending some time digging around my parent’s basement, delving into my assorted and sordid collection of ephemera.

The above scan is from a photocopy of a bound volume of Life Magazine. While college students today have numerous distractions available to them via cellphones and wi-fi, back in the olden days of 1990, all I had were the comics pages found in newspaper [1] microfilm [2] and the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature [3]. Hard to believe, but back then, the news media rarely covered comics, perhaps featuring one article every month or so!

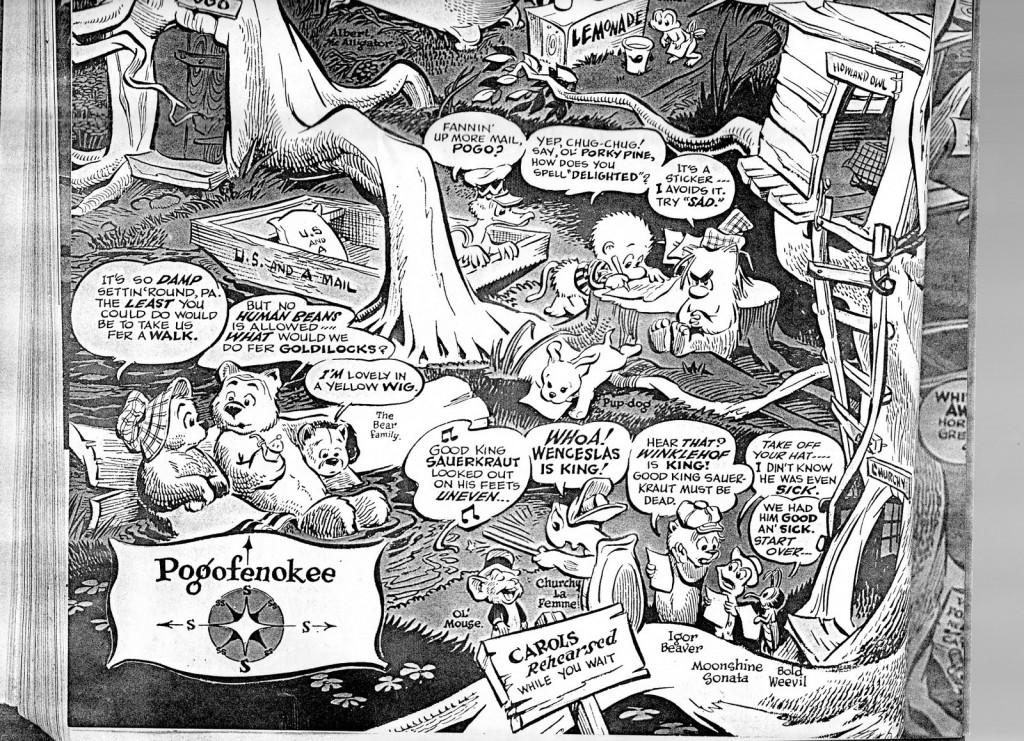

So, like any fanatic, I began to haunt used bookstores for other collections, and, when bored at the university library, scan the Readers’ Guide to find recent comics articles. Fortunately, the Readers’ Guide had annual volumes, so I only had to thumb through about forty volumes instead of 1,000! That’s how I found the above article, which appeared in the May 12, 1952, issue of Life Magazine. It profiles Walt Kelly and his popular comic strip, Pogo. Running from page 12 to 14 of that issue, it includes a stunning one-and-one-half page drawing of the swamp, populated with many of the swamp denizens, all in dialogue!

“Okay,” you say, “that’s pretty cool and all, but why should that interest me, a savvy citizen of the webbed-wide-world? I prefer indie and alternative comics which speak of the human condition and express the artists’ voice and vision, not some mass-produced comic strip pandering to the masses.” Well, aside from the scrumptious artwork, amazing lettering, and delightful dialogue, Walt Kelly was a pioneer among cartoonists. Twenty years before Doonesbury, thirty years before Bloom County, Kelly was frequently satirizing world figures and events on the normally benign comics pages of the nation’s newspapers. His caricature of Senator Joseph McCarthy as polecat Simple J. Malarkey, during the height of the McCarthy’s popularity as a anti-Communist demagogue, attacked McCarthy’s views a full year before Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now” documentaries. Many of his storylines, deemed unsuitable to the average newspaper reader of the day, were substituted by Kelly’s “Bunny Strips”, specifically designed to placate nervous newspaper editors, while still using the themes featured in the normal, more political, strips.

- gain the presidential endorsement of the Harvard (University) Crimson, which selected Pogo as their candidate of choice over Adlai Stevenson and Dwight D. Eisenhower

- appear on campus to a capacity crowd, and

- cause a riot of some 1600 students in Harvard Square, which halted streetcar traffic, and resulted in numerous acts of police brutality as the local police officers unleashed their simmering town-gown prejudices.

In 1952! In genteel, respectable Boston, Massachusetts!

Here’s an historical retrospective, from the Harvard Crimson, published in 1987:

Organizers planned for students to rally across from the Yard, in the spot where Holyoke Center now stands, and then march to the New Lecture Hall to hear Kelly’s speech. But things did not come off as planned.

Kelly’s arrival from Logan Airport was delayed, and the crowd on Mass. Ave. grew antsy. It also grew large. As the clock ticked on, the number of students milling about the Square waiting for Kelly multiplied from about 200 to 1600.

The density of the crowd increased and the traffic in the Square became terribly congested. The electric trolleys, still in use in 1952, could not make their way through the Square because of the students blocking the streets and the back-up of other traffic. A handful of students, perhaps for lack of anything better to do, began to disconnect the poles linking the trolleys to their source of energy on the wires overhead. Police rushed the crowd, beating and arresting students.

[Paul R.] Rugo, now a Boston attorney, says he remembers the evening “like it was yesterday.” Dressed in his ROTC uniform, Rugo says, he was walking down Mass. Ave. with his date, now his wife.

“I had nothing to do with the Pogo parade,” Rugo says. “All of a sudden it just erupted.” Outside of J. August and Co., policemen honed in on Rugo and told him he was under arrest. He received no response when he asked what the charges were against him. “The police swung furiously, and I swung back,” he says, adding that his flying punches landed him in the paddy wagon on his way to jail.

Five of the 28 Harvard students towed away by the police were Crimson editors. Meanwhile, Kelly arrived to deliver his speech, which was interrupted several times by spontaneous pogo stick races down the aisles of the auditorium.

Most defendents pleaded no contest, and most were given a minimal punishment.

Did this affect the graduates of Harvard, resulting in the counter-culture movement of the late 1960s? Or was it just a brief lark, spearheaded by a few bored students at the newspaper? I’ll let historians debate the importance of the “Pogo Riots” and its influence on post-war America.

Footnotes:

[1] a publication issued at regular and usually close intervals, esp. daily or weekly, and commonly containing news, comment, features, and advertising.

[2] thick rolls of plastic tape containing tiny photos of newspapers or other publications, usually magnified by means of a special display.

[3] Imagine Google News published every two weeks as a paperback, listing links from 400 periodicals.