In June 2016, DC Comics kicked off the start of its Rebirth initiative. After a wave of criticism surrounding the way they have treated their characters’ rich histories since 2011’s New 52 relaunch, DC has decided to rebrand. They hope that by restoring their characters’ pasts, they will restore readers’ faith in them as well. Do they succeed? That’s what the Comics Beat managing editor Alex Lu, entertainment editor Kyle Pinion, and contributor Louie Hlad are here to discuss. Book by book. Panel by panel.

THIS WEEK: Alex reviews the next phase in Young Animal as Shade the Changing Girl becomes Shade the Changing Woman #1. Plus, Alex dives into the central question posed by Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles #3.

Note: the reviews below contain **spoilers**. If you want a quick, spoiler-free buy/pass recommendation on the comics in question, check out the bottom of the article for our final verdict.

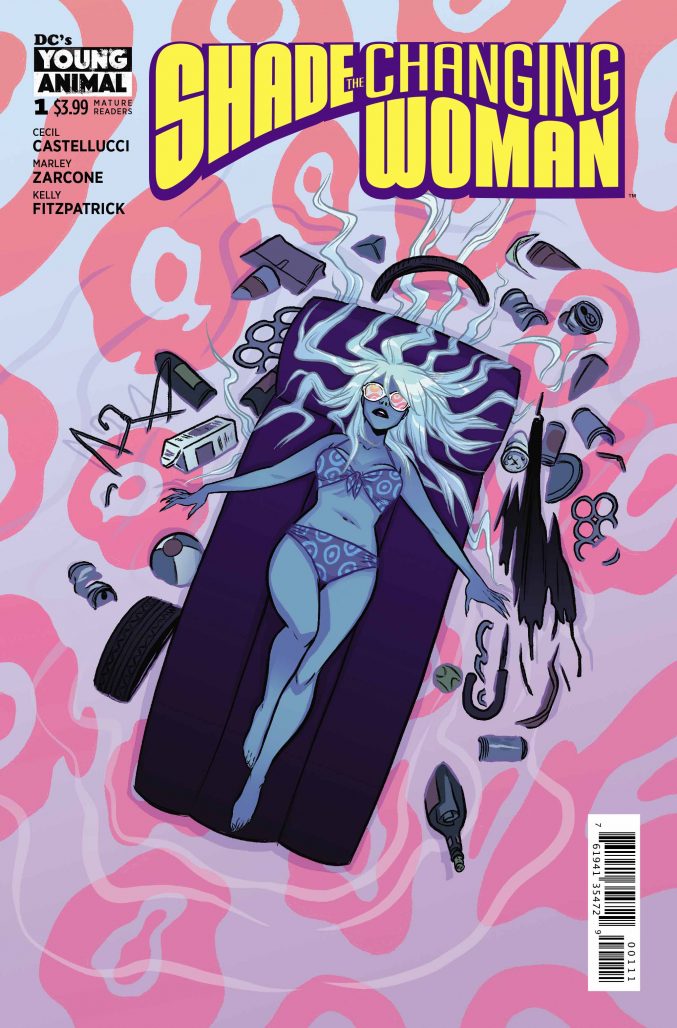

Shade the Changing Woman #1

Shade the Changing Woman #1

Writer: Cecil Castellucci

Artist: Marley Zarcone

Colorist: Kelly Fitzpatrick

Letterer: Saida Temofonte

One of the most fascinating parts about the Young Animal imprint thus far has been it’s ability to pivot. Unlike the mainstream DC Universe, which is weighed down by decades of history and expectation, Young Animal quickly learned to set only one expectation for it’s readers: that things could and would change. And fast.

The only constant about Young Animal was that things would be weird. And no book from the imprint’s initial lineup was weirder than Shade the Changing Girl, a fish out of water story about an alien named Loma who uses a magical madness coat to subsume the body of a teenage human girl. It was a trippy and evocative comic right from the start, thanks in no small part to artist Marley Zarcone’s abstract background art and Kelly Fitzpatrick’s luminescent neon colors. Pages filled with zoo animals and hospital workers who’ve been reduced down to their skeletons litter the very first scene of the series’ first chapter. It was a bold visual statement that promised a unique and slightly esoteric experience that the series has largely delivered on.

That said, while the visual stylings of the series have generally remained consistently weird, I went back to the first issue of Shade the Changing Girl recently and was surprised to see how much the storyline and themes of the series have grown and evolved over time. Gone are the days where Megan, the original owner of Loma Shade’s earth body, was at all an obstacle for Loma to face. Gone are the days where people perceived Loma as some sort of monster. Like most teenagers who didn’t quite fit in when they were growing up (raise your hands, folks), Loma found a few trustworthy souls to confide in and eventually left her small suburban nest in search of greater heights. And that was the story of Shade the Changing Girl— how an outsider teen learns to find herself and grow into her own skin. Basically Lady Bird for the weird kids.

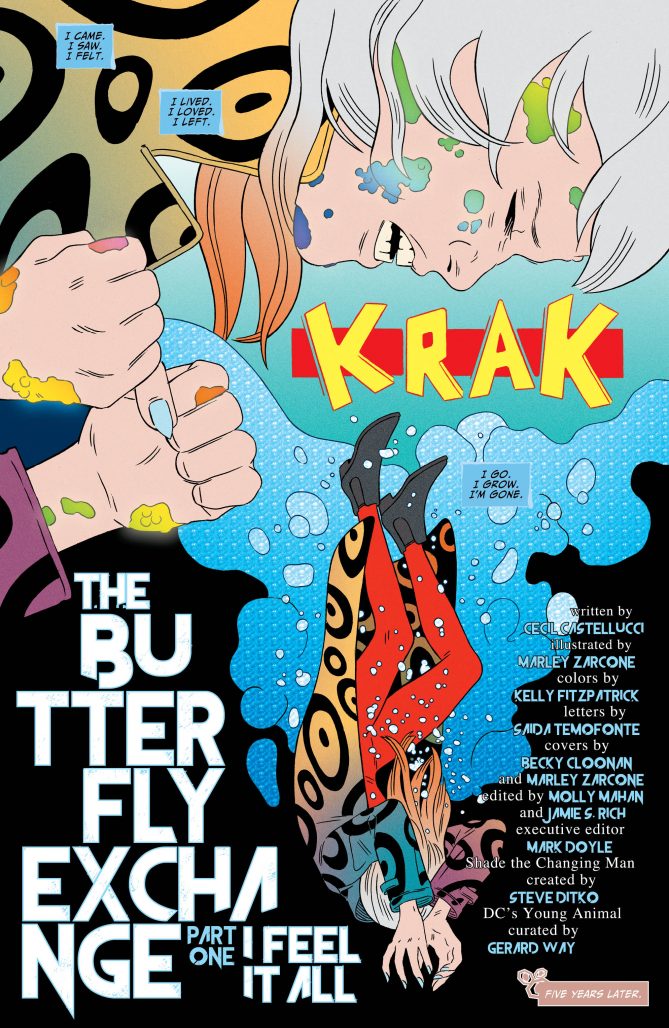

But that story is over now and we’re on to something new. Shade‘s creative team makes that clear from the start not just by the renumbering of the series but by its new name: Shade the Changing Woman. And if Shade the Changing Girl was a story about the young soul’s capacity for growth and reinvention, Shade the Changing Woman is definitively about the other side of that coin– a young adult’s capacity to regret and yearn for innocence lost.

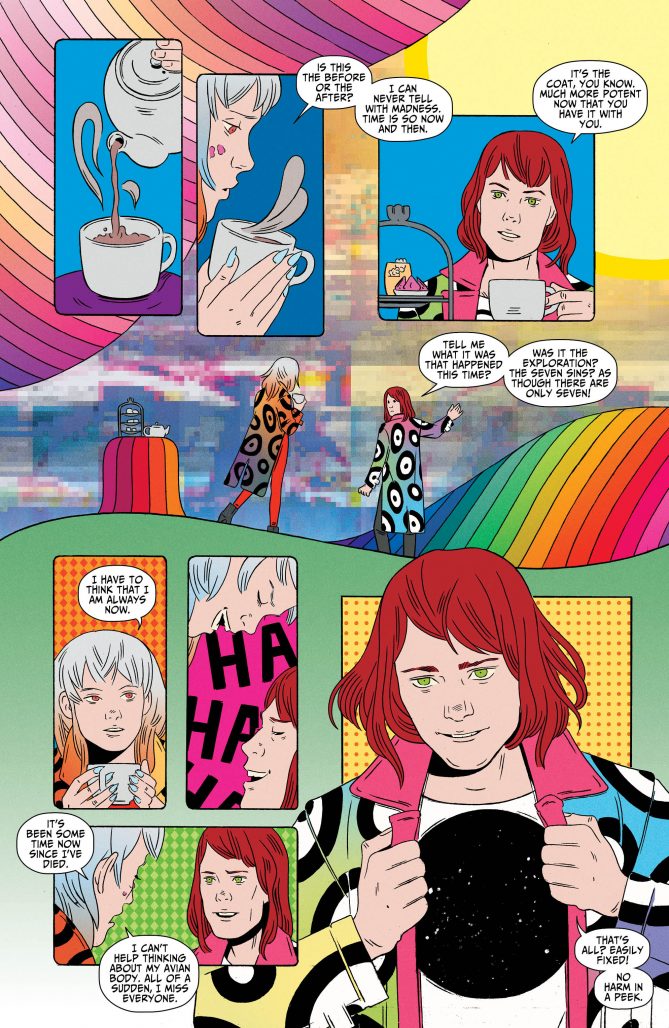

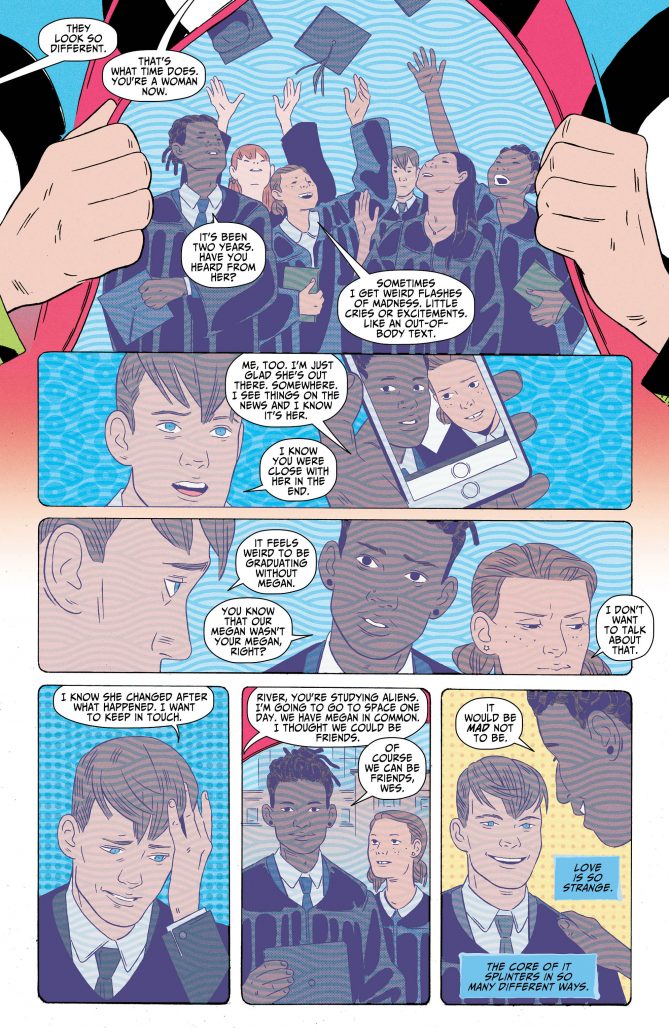

Between these two stories, a lot has changed in Loma’s life. Two years have past since her old human body died and was reborn as a more mature version of itself– a visual metaphor made very, very literal. After her rebirth, Loma ran away and has been living as a transient ever since. And in the meantime, her human friends River and Teacup have graduated high school and are about to move on to the crucible of adulthood: college. It’s here, on River’s first day at the Florida Institute of Technology, that Shade reenters her friends’ lives, catching them up on the things she went through on her two year journey away from him and Teacup– a series of ongoing events that the latter diagnoses as “an existential crisis.”

Indeed, Shade the Changing Woman #1 proves to be a broad and brooding existential crisis of a comic. It never quite commits to a specific social issue that it wants to address, hinting at a variety of conflicts instead through a series of fascinating artistic spreads throughout the book. Marley Zarcone and Kelly Fitzpatrick work together at their best to make these images shine. Through their work, we see themes of American political division, environmental destruction, human greed, and unreasonable female beauty standards expressed– and that’s just in two pages. In my favorite page of the story, Shade muses on the fickle nature of love and on how easy it is to take the objects of our affection for granted until they’re already “impossible and gone,” with Shade curled in a fetal position and gradually crying herself until she’s screaming in a sea of her own tears. If you prefer your stories tighter and more committed to diving deep into a specific topic, Shade the Changing Woman #1 probably isn’t the book for you, but there’s the sense that this book is a cathartic release of sadness and rage for the creators– and that’s something I, at least, can definitely identify with.

That said, there are still hints that the greater story arcs that Shade developed when Loma was a Changing Girl are still in play now that she’s a Changing Woman. At the end of Shade the Changing Girl the creative team reintroduced Rac Shade, the man who Loma and her series drew direct inspiration from. Loma used to see Rac as her idol and now he is her mentor, counseling her on the difficulties of existing as an entity without a proper home. And that sense of transience…of not quite belonging anywhere is still very much core to Shade’s character. We see that while, for a time, Loma was happier running away from small town where she first learned to be human, she carried her problems with her. Moving to a new place does not necessarily cure what ails you, Shade the Changing Woman argues. So, like in Lady Bird as the titular character reconnects with her mother, we see Loma turning to her friends. Perhaps looking back can offer what looking forward cannot, Shade seems to suggest. Perhaps there is a balance to be struck.

I would characterize Shade the Changing Woman #1 as less of a reinvention of Shade the Changing Girl and more of an evolution of the series. There’s some distinct thematic change to be found within this new debut issue that helps keep the book current with the time period of its release and with its growing audience, but its core is still very much the same as that of the book I fell in love with over a year ago. You owe it to yourself to check this one out.

Verdict: Buy

Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles #3

Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles #3

Writer: Mark Russell

Penciller: Mike Feehan

Inker: Mark Morales

Colorist: Paul Mounts

Letterer: Dave Sharpe

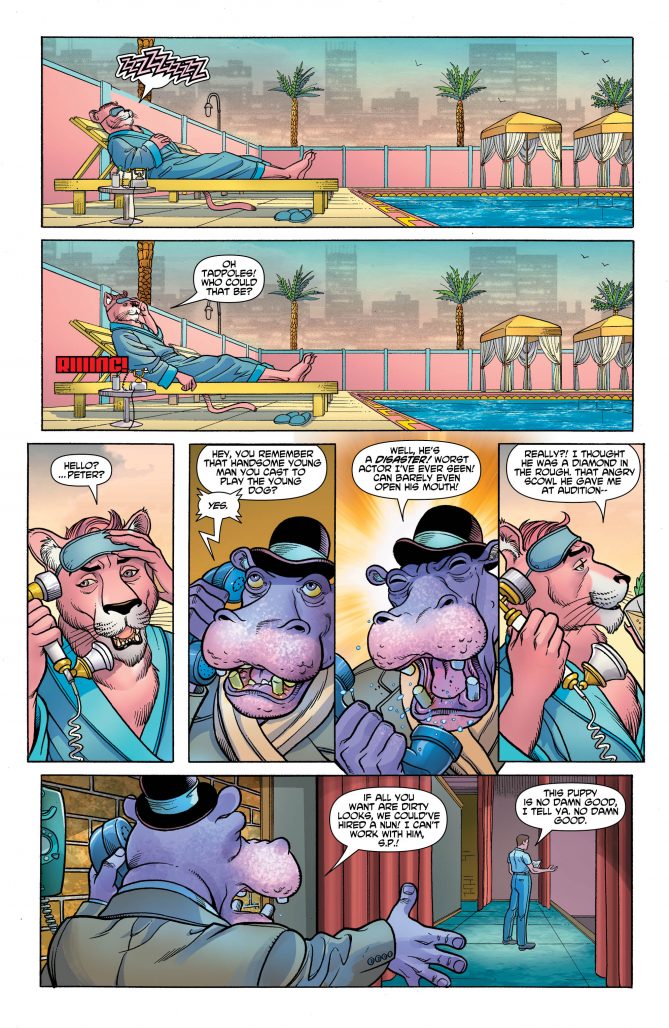

Thus far, Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles has proven to be a strikingly atypical period piece. While more standard historical narratives like recent Oscar nominated films The Post and Darkest Hour or comics like March attempt to turn history into narrative with a clear conflict and through line, Exit Stage Left has proven to be content to let the conflict lay in the background. The result is a strangely surreal yet naturalistic take on the era of American McCarthyism, where the trouble of the McCarthy media trials stirs and brews but takes a backseat to more immediate historical anecdotes in every issue. In this way, the core narrative conflict becomes a vehicle used to explore a variety of contemporary yet also currently relevant social issues rather than the being the main issue itself.

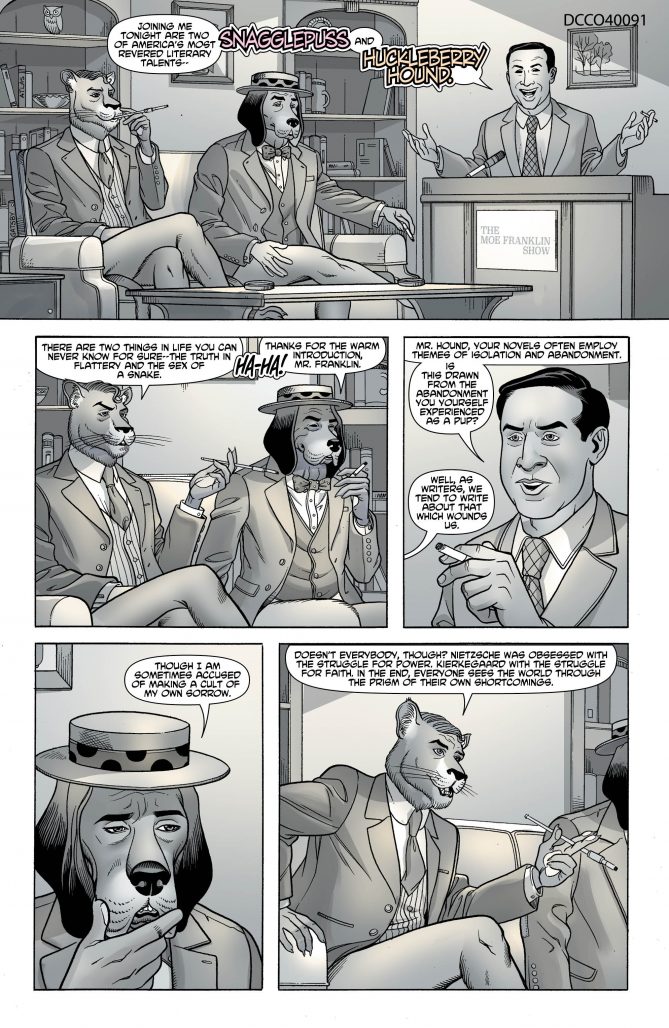

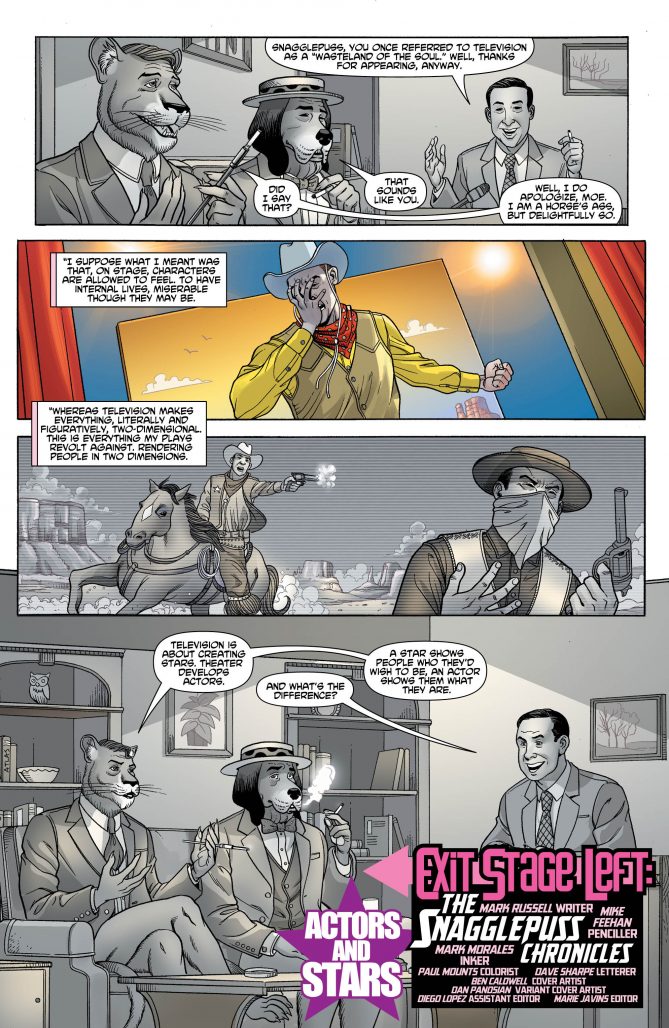

For example, in this week’s Exit Stage Left #3, we get barely a hint of Snagglepuss’ ongoing conflict with the House Committee on Un-American Activities or its special counsel, GiGi Allen, who was introduced to Snagglepuss in the last issue of the series. Instead, we see a variety of other conflicts unfold that center around a question introduced at the start of the issue: what is the difference between stars and actors?

According to Snagglepuss, the difference is simple: “a star shows people who they’d wish to be. An actor shows them what they are.” It’s the difference between looking up at an idol and looking down at your own reflection. And we see that difference in Marilyn Monroe’s (yes, that Marilyn Monroe) two suitors in this issue: playwright Arthur Miller and legendary baseball star Joe DiMaggio. In this fascinating use of history, the creative team behind Exit Stage Left puts three characters in a love triangle where they each see different versions of themselves reflected in their partners.

Between Miller and Joe, the differences are obvious. Miller is pleading, somewhat disheveled, small, and somewhat scholarly looking, whereas DiMaggio is brawny, angry, and dressed with a shirt and tie. Miller’s physique is that of an actor, whereas DiMaggio’s is that of a star. And DiMaggio sees Marilyn as a star as well, expressing to a diner waiter that despite the fact that everyone now loves him, “there’s a difference between being loved and belonging.” DiMaggio goes into his childhood as the son of immigrant parents who were “declared hostile aliens” the same year he was declared MVP of the American League. While DiMaggio might appear to be a star, he also sees himself as an actor– someone who is too different from the norm to find acceptance in the heart of America. And that’s why he loves Marilyn: “she’s everything I’ll never be.” She’s “the instant sweetheart of an entire nation.” She’s DiMaggio’s star and he believes, and we all do at some point, that stars could do no wrong. So of course DiMaggio’s jealous rage dissipates as soon as Marilyn walks into the bar with who she calls a known “sugarfoot” Snagglepuss. It’s a two dimensional lie, but it knocks DiMaggio down a peg because he wants to believe in his star.

Meanwhile, Marilyn, caught in the middle, expresses later in the issue that she “never wanted to be a star, [she] wanted to act.” She wanted to be a mirror, but she looked too perfect and seemed too perfect to be real. She became America’s sweetheart and someone that men like DiMaggio “need[ed],” losing her ability to express complexity to the world in the process. Which is why she wants to be with Miller, who Marilyn believes has never even seen a movie. He doesn’t need that Marilyn, she implies. He, as an actor, allows her to be the actor that she always wanted to be.

But the devil of this story is in the unexpressed details, I think.the interesting thing about this triangle is that while each of these characters only see one side of the others, they all express the capacity to be both actors and stars. Just as we all do. We all wear different masks around different people. We all curate digital personas to display the most attractive parts of our identities while bemoaning the deep-seated existential pain of our lives to our closest friends. We are compelled to categorize complex friends and family into simple roles that fulfill our needs. We turn our favorite writers, artists, actors, and musicians into stars. We dump our problems into loved ones we see as actors, neglecting the fact that they have star-like qualities too.

It’s a complex thing, Exit Stage Left. It’s a comic more content to dwell on an idea than it is to push towards a narrative goal. And it’s all the more compelling for it, I feel.

Verdict: Buy

Round-Up

Round-Up

- The last Batman issue felt like a surprisingly long prologue, but we really get down to business with Batman #42. The concept of a world run by Poison Ivy with Batman and Catwoman treated as two pets is quite funny to me, if a bit implausible. It’s a great excuse to see Batman go up against the entire Justice League– another equally implausible concept that I still find quite fun regardless. Mikel Janin clearly gets his kicks out of the issue, including a fantastic looking spread of Wonder Woman, Superman, and Green Lantern Jessica Cruz hanging the Bat and the Cat from the top of a sky scraper. It’s a really regal page that captures the sublime majesty of Ivy’s world. And I honestly can’t think of a better character for Janin to render than Poison Ivy, as one of her core tenets is this element of cheesecake that Janin’s photo-realistic style sells so well. Janin even gets to play against type a bit with a surprisingly grim and brutal splash that I won’t spoil here. This is sheer goofy Batman at its best– and while it definitely doesn’t sit perfectly with Tom King’s portrayal of Batman as something of a failed human, I’m totally here for it nonetheless.

- Priest is doing some excellent metafictional work in Justice League right now. In issue #40, out this week, the “Justice Lost” storyline continues as the elusive Fans continue to tighten their stranglehold over the world’s greatest heroes, bending them towards a purpose that they perceive the Justice League to have lost. While there’s a number of other meta elements at play here– some Civil War-esque critiques on the role of an independent body of armed soldiers on the world stage and some class-based critiques of how the law, justified or not, is often perceived to side with rich people and white people in America– the part that I think is most fully developed is this strangely brazen yet apt critique of comics readers who want their childhood characters to never change. It’s well worth a read, in my opinion.

From the art, I thought it was a woman showing the new Shade things, and I found that compelling (kind of like Promethea). It’s the original shade though, which makes sense, but I’m a little bummed. Haven’t read the previous tpbs yet to know if the book’s diffuse commentary on numerous topics is distracting or not. Art’s likable, and it’s definitely just finallt reading my tpbs and seeing.

Have to agree with Snagglepuss and ‘dwelling’ as the book’s substance. I hope so, and I’m now more excited for this than most other books.

Comments are closed.