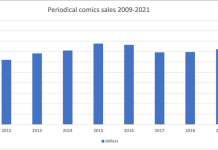

As he posted in the comments yesterday, Russ Maheras has run some numbers showing that despite millions of comics selling in the ’50s/’60s and 1000’s selling now, the industry as a whole is way more profitable now — say $600 million as opposed to $236 million. John Jackson Miller hosts the figures and breaks it down:

“According to your figures, in 1959, comics were selling about 26 million copies per month, or about 312 million copies per year. For the sake of argument, let’s use 10 cents a copy as the mean retail cover price (yes, there were some 15- and 25-centers on the stands back then, but we’re just trying to get a quick-and-dirty snapshot). That comes to a grand total of about $31 million in 1959 annual sales for the industry. Trade sales, film and television income, and other licensing income was negligible for almost all comics companies in 1959, and profits from video games did not exist.

“So that $31 million, plugged into the Department of Labor’s inflation calculator, is equivalent to about $236 million in today’s dollars.

Ancillary rights for comics add a lot of bucks to the till.

So as you see, despite the shrinking audience for most forms of entertainment, there is still a lot of money floating around.

Uh…you know that PROFIT and REVENUE are completely different things right?

The only answer that matters is whether or not the industry is profitable. If that 31 million in earnings cost 15 million (salary, production, distribution etc..) and today’s 600 million cost 595 million…then that tells you something way different than simply looking at inflation adjusted revenue.

First off, a quick note that that $239 million figure was Russ’s initial quote, which was based on the publishers that reported to the Ayer’s Guide; later in the piece, I write that the 1959 market size was maybe as much as a third larger.

And obviously, we’re talking about the overall price tag for goods sold. I don’t think there are many qualified to be able to figure what the profit margin was in 1959. But we can certainly guess that retailers are talking a bigger piece of the pie than they were in 1959, given the direct market — and that creators are, too.

The exercise Russ began was a simple comparison of merchandise values; there’s plenty of room for others to elaborate.

What’s the inflation calculator on the price of a 10 cent comic? Is it $3.99 – 2.99?

One note on population size: In 1960, the U.S. population was about 180,671,158; now, it’s about 310,956,694.

SRS

Nope, it’s just 72 cents. I get into that a bit in the piece — the reasons comics have outpaced inflation. (In some measure, they’re not equivalent packages any more.)

Which is why we should be wary of comparisons that touch only on a single statistic, this one included. The total amount paid for all comics is higher now than it was in 1959, adjusted for inflation — which is Heidi’s headline here — but there are fewer goods being bought, and by fewer people. I tried to get into those elements in the piece.

What’s this, a piece of the Beat suggesting that print comics maybe aren’t dead? Is this Bizarro Beat?

A modest revision to the above post, as well: while there were comic books that sold in the millions in the 1950s, only UNCLE SCROOGE and WALT DISNEY COMICS & STORIES did so in the 1960s, and then only in 1960:

http://www.comichron.com/yearlycomicssales/1960s/1960.html

It’s possible a single issue or two of BATMAN broke the seven-figure barrier during the TV show, but the next confirmed million-seller aren’t until STAR WARS #1-3 in 1977 (and those were mostly later printings).

MAD was selling in the millions all through this time, of course.

@John J Miller – sorry, I missed that part. Not enough coffee in the system.

No problem — I would have thought the difference was more, myself. But there’s yet another caveat: that inflation calculator deals with the purchasing power of the dollar, and not the increases in costs of things like paper over that time, which may or may not have also outpaced inflation. (Even if they haven’t, we’re using much better grades of paper now, which speaks to what I wrote about the two packages not being equivalent.)

Oh John Jackson Miller, for once I try to be positive, as Ryan suggests, and I am wrong there too! OH WHAT IS TO BE DONE!

Folks can argue comic book sales numbers then vs. numbers now, and how the comic book audience (for floppies) has shrunk, and how that’s bad (I made a similar arguments myself in my fanzine Maelstrom), but with all of the spin-off popular culture outlets for comics characters now, comic books are more in the public eye than ever before. Even more important, comic books and their spin-off outlets are far more accepted by the general populace than at any time in comics history — which is why, I guess, comics-related material is generating so much more money now.

Sorry, Heidi. You’re right — on the day when we’re potentially looking at San Diego hotel rooms in Carlsbad, we should try to stay upbeat!

Russ, I actually posted about this on my blog today. Yes, awareness and acceptance are probably at an all-time high. And yet, comic book stores sell about the same amount of comics as they did 10 years ago. And as is pointed out above, less people are buying more per person than they were in 1959. While I’m glad to see the industry generating more money than it did 50+ years ago, it doesn’t really seem to be expanding its audience. In fact, it’s contracted in spite of all of these potential revenue streams. Why aren’t the spin-off outlets and acceptance from the general populace resulting in more people going to comic book stores? Are they too scary for the general populace? For some, I’m sure. But it seems like there should be some uptick with everything out there. I guess there’s also the economy, but even so.

I don’t think I see what’s probably a large debit for the 1959 numbers, which is the cost of returned copies. There’s a good chance that cost reduces their profitability even more.

But I strongly agree with the phrase “we don’t just want dollars, we want eyeballs”. I think that the 1959 market was constantly adding new readers because of the easy accessibility of comics… and that really paid off in the 1960s and 1970’s. Adding those new readers is a problem that the Direct Market doesn’t solve at all, as I see it.

So what was a pretty profitable and growing business in 1959 looks like a (possibly) more profitable, but shrinking, market in 2011, with the usual sinister overtones for its future in the next few decades.

Corey — While the traditional floppy audiences have waned, audiences for graphic novels (and I’m not talking repackaged Marvel/DC compilations), manga, and video games have exploded.

These are all comics derivatives, in my opinion, as are films like Shrek, Toy Story, The Incredibles, Megamind, etc.

Face it… is there really that much of a difference between a comic book like “Men in Black” spinning off into a movie, and “Gears of War” spinning off from a video game into a comic book?

This die-hard comics fan hates to admit it, but, depending on my mood on a given day, I’d much rather play, say, “Dead Space 2” than read a 2-D comic book about of Isaac Clarke’s never-ending battle against the necromorph scourge.

My belief is that the audience for printed comics has grown in the last 10 years. Yes, the 70-80 million comics annually sold through comics shops hasn’t changed (though it did improve for a while in the mid-2000s). But what did grow is the audience for trade paperbacks, and the majority of buyers found those outside the direct market.

Yes, we should ask why the existence of those new readers hasn’t boosted the number of periodicals sold. I can think of two responses: (a) they HAVE brought in customers, but just enough to replace the turnover in periodical readership, or (b) since those readers are demonstrably buyers of collected editions, maybe that’s the format they prefer. I think as we add digital options, we’ll need to look at the TPB experience to see what might happen.

And Bradley — yes, you’re absolutely right on returns and the 1950s; enormous sums were spent to print comics seen by no one. “Print three to sell one.” Today’s returnability is at least mostly confined to trades, which aren’t limited to just a month in which to sell through.

John I agree that there has been some growth outside the direct market. I think it’s a shame that the direct market has apparently been unable to take advantage of it (or take advantage of it enough to not simply replace who leaves).

Multiple publishers we spoke with at last year’s Comic-Con (for a supplemental piece to the Dig Comics documentary) gave startling figures about to what extent the book market does so much better for them in comparison to the direct market. Because of this, and the early fast growth of digital, I don’t think comics as a form of communication is going anywhere. Comic book stores on the other hand… Well, they’re holding the line for now, I guess. That is something, at least. Especially in this economy.

Russ, I agree with you in part as far as the derivatives of comics. But the comics form as a language is unique and what interests me. Comics are comics whether they’re adapted and/or licensed from some property or are original stories. But movies and video games use different communication tools, so I don’t really think it’s part of the comics world beyond sharing story concepts or licensing deals.

Also… when a trade paperback is returned, it isn’t a stripped copy, like a mass market paperback. Eventually, that returned copy is sold. Either to another customer a few months later, or via the remainders market where a publisher will clear dead stock by selling by the crate or pallet, usually at a steep discount.

In bookstores, new titles usually have three months to sell before a book can be returned. It is rare that a hardcover title will sell consistently until the paperback is issued a year later. Michael Crichton was one of the few authors who achieved this feat.

Corey wrote: “movies and video games use different communication tools”

The way I see it, if you distill comics, films/cartoons and video games down to their essence, they all communicate the exact same way: scene by scene.

Thus, a master comic book/comic strip artist and a master film/video game/cartoon director have very similar approaches: they manipulate space and time, scene by scene, to evoke an emotional response from their audiences.

Call me simplistic, but as a comic book artist myself, I see very little fundamental difference between the three mediums. After all, a comic book is nothing more than the equivalent of a cinematic storyboard.

Huh, interesting. But with the “scene by scene” bit, I think you might be talking more about the nature of telling a story.

Don’t books communicate scene by scene? Radio plays? Anything with a narrative, really.

I tend to lean toward Scott McCloud’s view of how comics work. The information is experienced in a different way than the “moving pictures” forms. As a reader, I can see the entire page all at once instead of one precise moment at a time. And that effects how my brain processes the information and story. As a viewer, everything is presented to me one after the other at its own controlled speed.

Anyway, I guess this is getting more into theory and is probably off-topic from this article. But thanks for responding. Interesting stuff.

P.S.

Comics shops are independent specialty book stores. As publishers shift under-performing titles to a digital-only format (with a trade collection later), the selection of magazines offered will dwindle. So the store must promote the trade collections, as well as develop sidelines such as toys, apparel, videos, and snacks. As well as offer exceptional customer service and community events (artist jams, gaming, author signings…)

I was aware that comic book sales hit low points in the ’70s, but some online musing about comics sold then and now indicates that the situation was worse than I thought. Sixty-five percent of all the comics Marvel published in the ’70s returned unsold!? Marvel’s low sales point was said to be 5.8 million copies sold in 1979.

SRS

Sixty-five percent is probably close to correct — you can see that Spider-Man’s returns were closer to 50% here…

http://www.comichron.com/titlespotlights/amazingspiderman.html

…but that was a major title, and there were others that did worse.

The 5.8 million figure for 1979 is hard to figure, though. Marvel failed to put sales figures into many of its titles that year, but Amazing Spider-Man, Incredible Hulk, and Star Wars would EACH have been good for close to 3 million copies annually.

Maybe Daniels meant that figure was monthly?I don’t have the list for 1979 on my site yet, but scanning my database, I find Marvel had 3.5 million copies selling a month in 1979 just of the major series. Maybe when you throw in all the little bimonthlies Marvel was doing, it could get to 5.8 million copies — I’m not sure. (And, yes, that many a month is more than the whole DM sells some months now — but back then when they were mostly returnable, those figures were seen as calamitous.)

Re: Comic book sell-throughs during the 1970s…

Because comics were at the bottom of the periodical food chain during the 1970s, it was virtually impossible for any comic book to sell out.

I worked for Charles Levy Circulating Company in Chicago during the 1970s, and CLCC was the only distributor for what was then the second largest periodical market in the country.

The way the comics were distributed went something like this: On comic book distribution day, all the new comics that had been received up to that point were stacked on both sides of a conveyor belt. Order pickers flanked the belt, and as the orders slowly came by, the pickers looked at the order amounts for the titles they were picking and stacked them behind the order. At the end of the line, the order bundles were strapped and put on carts, and the carts then went out to the dock to be loaded on the trucks the next morning.

I don’t know who decided how many copies of each comic went to a vendor, but what I do know is that we usually always had comics left over, and those comics went down a chute to an underground conveyor belt that led to an enormous shredder. So it was kind of a bizarre twist of fate that I, a die-hard comics collector, had to routinely shred hundreds or thousands of undistributed comics each month as part of my normal job.

Bundles of magazines left over after the initial distribution orders were filled usually went to the re-order section (where I worked) in case there were later dealer re-orders during the month for a hot-selling magazine.

However, that was never the case for standard comics. What that meant is that if, say, only 70 percent of the Chicago allotment for “Amazing Spider-Man” was distributed in a given month, even if every single distributed copy was purchased throughout Chicago, the best sales Marvel could hope for in Chicago was a 70 percent sell-through.

I’m sure Marvel, DC, and the few other companies selling comics during the 1970s were constantly pressuring CLCC to maximize distribution for their titles, but if the vendors didn’t want a glut of some unknown title like “Nova” #1, the vendors didn’t want them. The margins for comics were pretty damn small for dealers back then (in 1976 a retail dealer made about six cents on every standard comic sold), so they were just not a high priority for many vendors.

Why aren’t the spin-off outlets and acceptance from the general populace resulting in more people going to comic book stores?

The TV and movie versions are easy to access. The comic versions are not due to the continuity pron and focus on pleasing the hardcore fanboys.

So when people whose kids liked, say, the Young Justice cartoon, do manage to find a place selling comics they see Green Arrow’s sidekick high on drugs and cuddling a cat corpse and they go home to wait for the DVD to come out instead.

So, if comic shops are specialty bookstores and are gearing toward trades…

And as a consequence, the print periodical end of the market is shrinking…

Doesn’t it make sense for publishers to create larger, less-expensive magazines to fill the gap as digital takes hold?

Well, the market for magazines of all sorts (which includes comics) is shrinking. If Disney Adventures, with a large circulation, can be cancelled, then what about comics magazines?

Digital is the new newsstand. Digital comics will replace periodical comics, ESPECIALLY when a customer can purchase a digital download for $1 cheaper than the print edition, via Diamond Digital.

Define “less expensive”.

Marvel Super Action

104 pages

$9.99

Too expensive? Almost the size of five comic books (22 pages = one comic), containing eight stories, no ads.

Then there’s the Disney comics paperbacks in Europe…

Lustige Taschenbuch is a paperback of 256 pages, selling for 4.99 Euros ($7.00).

Micky Maus sells for E2.30 ($3.25) in Germany, 64 pages, each week, plus a premium attached to each issue!

From a physical package point of view:

Switch out all of this high-gloss or the thick matte paper stock to the same white newsprint used for WEDNESDAY COMICS.

Say 96 +/- pages of which 80% pages are content and the rest is high profile advertising.

Price? $2.25 ( # pulled directly from my colon)

I don’t think it’s going to work for everything – but certainly there needs to be some sort of inexpensive format out there. If not, there’s going to be a growing disparity as to where people get their comics, and digital – because of price, convenience, ease of production and monetization – is going to win.

People will choose price and convenience. Comics as we know them today will become further and further marginalized (despite the higher media profile) and the Direct Market will collapse. Comic shops must be prepared for this. This is especially true when you can buy a Nook for $200 and hack it to run Android so you can read all sorts of formats, email, listen to music and eventually play games. In essence, have a $200 IPad.

The person who succeeds isn’t the one who knows where his business is now, it’s the person who knows where his business will be in the future and is prepared to meet it. The future is in digital, but it’s going to take a few steps to get there. In the meantime, publishers and comic shops need to get more and more people through the doors with “large and cheap” and then transition toward showing clientele all the cool collector’s trades of the digital comics they’ve been reading.