“I’m glad mainstream culture is starting to catch up to where lesbian-feminism was 30 years ago.”

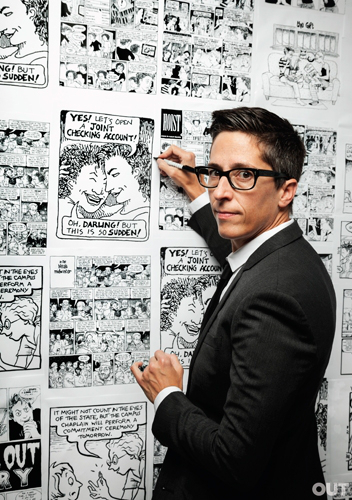

In the blog section of her Dykes to Watch Out For website, the comics creator and feminist hero addresses the latest hubbub surrounding the infamous Bechdel Test and its position in a new rating system adopted by progressive movie theatres in Sweden.

The actual story is very simple: four cinemas in Sweden launched a new rating to inform people of whether or not a film passed the Bechdel Test.

The test, for those not familiar, was first mentioned in a Dykes to Watch Out For strip in 1985, and acts as a measure for whether or not a film can manage to do the following: have two (named) female characters; have those characters speak to each other; and have them speak to each other about something other than a man.

It sounds relatively easy, but a huge percentage of films do fail this simple test. Which is what the test really serves to illustrate – not whether or not an individual film is perceived as sexist or misogynist (many factors must be taken into account), but in showing how rare it is for films to have women in them who speak of something other than a man.

To add further clarity, one can simply reverse the test and see how many films feature two named male characters, who speak to each other, and who speak of something other than a woman. The difference between the two results is rather telling. (This is a method I named the Reverse Bechdel Test, which I employed in a short study of the Bechdel Test upon DC and Marvel comics in May last year – a study I would very much like to expand upon in the near future!)

The Swedish cinemas have added this rating, alongside standard ratings that already exist for films – eg age certificate, warnings of violence, nudity or sex, and so forth.

What the rating does not do is censor what films can be made or shown, demand that films must feature women talking to each other about shoes, or dictate what directors can or should do. Yet a read of the comments and social media that the Guardian article spawned might make you think otherwise.

Bechdel writes in her blog post that she was more than happy to back the Swedish endeavour, but has turned down media requests for comment (after the first few) as it is tiresome to go over this same old (very old!) ground, and have to defend the cinemas against non-existent charges like those of censorship.

What she does write though is well worth reading in full. Here’s a snippet:

I have always felt ambivalent about how the Test got attached to my name and went viral. (This ancient comic strip I did in 1985 received a second life on the internet when film students started talking about it in the 2000′s.) But in recent years I’ve been trying to embrace the phenomenon. After all, the Test is about something I have dedicated my career to: the representation of women who are subjects and not objects. And I’m glad mainstream culture is starting to catch up to where lesbian-feminism was 30 years ago. But I just can’t seem to rise to the occasion of talking about this fundamental principle over and over again, as if it’s somehow new, or open to debate. Fortunately, a younger generation of women is taking up the tiresome chore. Anita Sarkeesian, in her Feminist Frequencies videos, is a most eloquent spokesperson.

I speak a lot at colleges, and students always ask me about the Test. (Many young people only know my name because of the Test—they don’t know about my comic strip or books.) (I’m not complaining! I’m happy they know my name at all!) But at one school I visited recently, someone pointed out that the Test is really just a boiled down version of Chapter 5 of A Room of One’s Own, the “Chloe liked Olivia” chapter.

I was so relieved to have someone make that connection. I am pretty certain that my friend Liz Wallace, from whom I stole the idea in 1985, stole it herself from Virginia Woolf. Who wrote about it in 1926.

Which goes to show that women have been shouting the very same things for a long time, only for it to be newsworthy then and again before being conveniently forgotten so that it may be whipped out again to churn up some headlines.

The cinema directors and their supporter, the Swedish Film Institute, are getting a large amount of uninformed abuse in the fallout from this story, but what they have done is remind people of the huge gender disparity in our media, and that even informing people of that disparity generates an incredibly hostile reaction.

A reaction that is perhaps more telling than any test could hope to be.

Heidi, someone went and applied BIG DATA to the Bechdel test with some interesting results:

http://tenchocolatesundaes.blogspot.com.br/2013/06/visualizing-bechdel-test.html

Er Laura that is. :)

Cheers for that Rob!

I should also note that there is the Bechdel Test Movie List where you can search for films to see their rating, or indeed add ratings of your own.

Thank God someone finally mentioned Virginia Woolf–even better that it was Bechdel herself. That was always one of my big annoyances with this whole phenomenon. How could this test, which is at most a rewording/simplification of a critical argument in one of the most famous pieces of writing in feminist history, become known under another writer’s name? Perhaps Woolf, too, was drawing on other sources, but leaving her name out completely would be worse than, say, lionizing Kanye West for “Stronger” without ever mentioning either Daft Punk or Nietzsche.

My other annoyance with the Woolf/Bechdel test is the temptation some might have to confuse it with a standard of quality. Certainly films can pass the test, as Bend it Like Beckham does, and still be quite bad (YMMV). A great film may have no significant female characters. The test can be enormously revealing as a tool of cultural critique, but it has little or nothing to say about whether any one film is worth watching (which makes its application in Sweden of very limited utility, it seems to me). I can imagine there are viewers who care more about a film’s position in social history than its intrinsic values (maybe you just can’t stand to watch one more story of brilliant men, even if it’s on the level of The Social Network), but–and I recognize this may just be my white male privilege speaking–I care more about seeing a good film. So I’ll always give far more weight to the opinion of a trusted reviewer than to the results of the “Bechdel test.”

That said, I haven’t read any of the comments/backlash mentioned in this article, but I’m sure Bechdel was undeserving of them.

But Chad, I would argue that the test is very useful – sometimes a person wants to watch something that isn’t, you know, 100% about men. Not that there’s anything wrong with men! But imagine almost everything in fiction was, in one way or another, about women. Wouldn’t it be refreshing when you got some variety?

It has been known for ages that reality inspires fiction and fiction influences reality. Nowadays, fiction is called media, but nothing changes – media does reflect current situation! Frequency and portrayal of women does in large depend on women, and their motivation to roll up their sleeves, and not their skirts to get the job done. It is OK to point out the disparities in presentation and representation, but feminist would serve their cause better if they would turn their effort to influencing women in the direction of participating more and trying harder, not just to obtain positions of power through politics, but to earn them through hard work and acquiring more knowledge. For feminists and supporters, I have devised a simple test – just look around and try to find an object that a woman created, and you are going the realize that if contributions of men were disregarded we would still be living in caves. When that changes, the portrayal of women will do too. It is the difference between being present and contributing.

Comments are closed.